Rick Mills – “China Stealing Rare Earths Monopoly from US is all About the Missiles”

Americans might be surprised to learn that China possesses 80% of the rare earth elements (REEs), and almost 100% of the technology used to refine the oxides and then manufacture such essential military equipment as night vision goggles, guided missiles, fighter jets and sonar systems.

To wit, American armed forces are almost totally dependent on the very country that is widely viewed as America’s greatest economic and military threat.

The historical record shows that it should have been the United States that dominates the mining, processing and refining of rare earth elements, not China.

A brief history

During the 1980s, General Motors secured multi-million-dollar grants from the Pentagon, which it used to develop permanent magnets from rare earths for its vehicles.

There are six types of permanent magnets, but only two are made with rare earth elements: neodymium-iron-boron magnets, and samarium-cobalt magnets. The other four types of magnets are ceramic (or hard ferrite), alnico, injection molded and flexible.

REE permanent magnets became the magnets used by major American industries. But their success created a new problem. By 1986, GM was finding it increasingly difficult to keep up with demand for permanent magnets, so it created a separate division, Magnequench, assigned to make the magnets in a facility in Indiana.

Meanwhile China, aided by decades of government funding of domestic mining for heavy and light rare earth elements, along with cheap labor and lax environmental standards, by 1994 had surpassed the US in the mining of rare earth elements.

Their problem was they lacked the technical expertise to refine rare earths into permanent magnets. They would soon find a way to address this, through the acquisition of GM’s Magnequench.

In just seven years leading up to 1994, Magnequench attained global control over the production and sale of permanent magnets. (Gazette)

The source for the rare earths was the Mountain Pass mine in California.

Previously little happened at Mountain Pass, but that all changed in the 1960s with the color TV. The discovery of europium, which emits a brilliant red light when bombarded with electrons, ushered in the age of technicolor, and Mountain Pass, which had abundant europium, flourished. Rare earths mined there were also used in medical scanners, lasers, fluorescent lights and microchips.

In 1980, a misclassification of rare earths had catastrophic consequences for US rare earths mining. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the International Regulatory Agency amended the definition of “source material”, classifying all rare earths found in monazites and other thorium-bearing ores including heavy rare earths, as a precursor nuclear fuel.

It’s important to understand that the NRC classified rare earth mining as radioactive not because the elements themselves are radioactive, but because their ores contain naturally occurring radioactive elements like thorium and uranium.

Thorium, for example, drops out when processing heavy rare earth minerals like monazite.

New, onerous regulations on thorium made the mining and refining of thorium-bearing rare earth elements risky. Heavy rare earths critical to national and energy security could no longer be extracted and processed due to the elevated radioactive (uranium, thorium) content.

Why was this decision made and who made it?

In 1980, the head of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) was John Ahearne. He served as the chairman from December 7, 1979, to March 2, 1981. Ahearne, a Democrat, was appointed as the interim chairman by President Jimmy Carter in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island (TMI) accident in March 1979.

Source: Nuclear Newswire

Source: Nuclear Newswire

While only speculation, his agreement with the NRC on re-classifying rare earths as a precursor nuclear fuel, which led to the cessation of rare earths mining in the US, could have been due to his experience dealing with the Three Mile Island nuclear fallout.

Over the next two decades, due to the existence of thorium or uranium in rare earth mine tailings — elements now heavily regulated, including strict nuclear waste handling and storage procedures — the US rare earth mining industry collapsed.

Then in the 1990s, the Mountain Pass mine ran into trouble.

Owner Molycorp faced legal action in 1997 after it was discovered that spills from its wastewater pipes had contaminated the Mojave National Preserve with trace amounts of radioactive thorium, barium and uranium.

It was around this time that China started a program to develop its own rare earths. The Chinese began mining the massive Bayan Obo mines north of Baotou, Inner Mongolia — containing an estimated 70% of the world’s rare earths reserves. A flood of Chinese rare earth oxides into the market hurt Molycorp, which shut down its processing facility in 1998.

The Magnequench saga

China wouldn’t have been able to develop its REE industry if it wasn’t for the dubious acquisition of Magnequench, a division of General Motors established in 1986. In 1982, General Motors research scientist John Croat created the world’s strongest permanent magnet using rare earths. The purpose of Magnequench was to produce neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, a superior type of permanent magnet that GM needed for its vehicles.

In 1998 Indianapolis-based Magnequench was mysteriously sold to members of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s family. The facility was then shut down and moved to China in 2000.

(The connection with the Deng Xiaoping family was through the Sextant Group, which purchased Magnequench from GM. Sextant was a front for two Chinese companies with close ties to the government, which it is believed targeted Magnequench for developing its long-range cruise missiles).

For the fascinating story of how Magnequench and its technology was ceded to the Chinese, read a 2006 article by Jeffrey St. Clair. Below is an excerpt:

“Magnequench began its corporate life back in 1986 as a subsidiary of General Motors. Using Pentagon grants, GM had developed a new kind of permanent magnet material in the early 1980s. It began manufacturing the magnets in 1987 at the Magnequench factory in Anderson, Indiana.

In 1995, Magnequench was purchased from GM by Sextant Group, an investment company headed by Archibald Cox, Jr – the son of the Watergate prosecutor (Cox Sr was an advisor to then-Senator Kennedy on labor legislation, served on his 1960 presidential campaign staff, and was later appointed as Solicitor General by Kennedy in 1961). After the takeover, Cox was named CEO. What few knew at the time was that Sextant was largely a front for two Chinese companies, San Huan New Material and the China National Non-Ferrous Metals Import and Export Corporation. Both of these companies have close ties to the Chinese government. Indeed, the ties were so intimate that the heads of both companies were in-laws of the late Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping.

At the time of the takeover, Cox pledged to the workers that Magnequench was in it for the long haul, intending to invest money in the plants and committed to keeping the production line going for at least a decade

Three years later Cox shut down the Anderson plant and shipped its assembly line to China. Now Cox is presiding over the closure of Magnequench’s last factory in the US, the Valparaiso, Indiana plant that manufactures the magnets for the JDAM bomb. Most of the workers have already been fired.

“Archie Cox and his company are committing a criminal act,” says Mike O’Brien, an organizer with the UAW in Indiana. “He’s a traitor to his country.”

It’s clear that Cox and Sextant were acting as a front for some unsavory interests. For example, only months prior to the takeover of Magnequench. San Huan New Materials was cited by US International Trade Commission for patent infringement and business espionage. The company was fined $1.5 million. Foreign investment in American high-tech and defense companies is regulated by the Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS). It is unlikely that CFIUS would have approved San Huan’s purchase of Magnequench had it not been for the cover provided by Cox and his Sextant Group.

One of Magnequench’s subsidiaries is a company called GA Powders, which manufactures the fine granules used in making the mini magnets. GA Powders was originally a Department of Energy project created by scientists at the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Lab. It was spun off to Magnequench in 1998, after Lockheed Martin took over the operations at INEEL.

In June 2000, Magnequench uprooted the production facilities for GA Powders from Idaho Falls to a newly constructed plant in Tianjin, China. This move followed the transfer to China of high-tech computer equipment from Magnequench’s shuttered Anderson plant. According to a report in Insight magazine, these computers could be used to facilitate the enrichment of uranium for nuclear warheads.

GA Powders isn’t the only business venture between a Department of Energy operation and Magnequench. According to a newsletter produced by the Sandia Labs in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Sandia is working on a joint project with Magnequench involving “the development of advanced electronic controls and new magnet technology”.

Dr. Peter Leitner is an advisor to the Pentagon on matters involving trade in strategic materials. He says that the Chinese targeted Magnequench in order to advance their development of long-range Cruise missiles. China now holds a monopoly on the rare-earth minerals used in the manufacturing of the missile magnets. The only operating rare-earth mine is located in Batou, China.

“By controlling access to the magnets and the raw materials they are composed of US industry can be held hostage to Chinese blackmail and extortion,” Leitner told Insight magazine last year. “This highly concentrated control-one country, one government-will be the sole source of something critical to the US military and industrial base.”

— Jeffrey St. Clair, ‘The Saga of Magnequench’

China’s acquisition of Magnequench was part of a long-term Chinese strategy to develop its rare earth industry by gaining control over critical magnetic materials and the technology to manufacture them, a process that allowed it to dominate the global supply chain for magnets.

It was also part of China’s broader, long-term strategy to develop its rare earth industry and secure control over the supply chain for high-energy magnets, which are critical for defense and high technology. China successfully used this acquisition to gain the technology and know-how to manufacture these magnets domestically. (AI Overview)

In 1992, while visiting a rare earths mine in Inner Mongolia, Chinese President Deng Xiaoping famously said, “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths”.

The final nail in the coffin for US rare earths came in 1998 when the US National Defense Stockpile sold the entire strategic reserve of rare earths. Since then, rare earth metals, alloys and magnets needed by US defense contractors come either directly or indirectly from China.

In 1998 Democrat Bill Clinton was in his second term and the Republican Party controlled both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Magnequench has left the building

How the US lost the plot on rare earths

For a detailed timeline of China’s rare earth restrictions and strategic moves, click here. And for the report, ‘China’s rare earths dominance and policy responses’ click here

The story of how Magnequench ceded control of its rare earths-processing into magnets know-how to China is familiar to some readers. Less known are the details: Who were the main players, why was control over rare earths given to China, and what were the consequences? It is to these questions that we now turn our attention.

Neo Performance Materials

The first question is what happened to Magnequench after its US operations were shuttered and moved to China? At the G7 summit in Kananaskis, Alberta this year, a magnet from Neo Performance Materials (NPM) was exchanged as a gift between EU President Ursula von der Leyen and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney — ostensibly to show that rare earth magnets can be manufactured outside of China.

Not quite what you think Mr. Carney

The firm has reportedly started construction on a new sintered magnet plant in Estonia, with capacity for 2,000 tons annually. This plant would be able to handle the processing of heavy rare earths, specifically dysprosium and terbium. While only comprising 1-2% of a permanent magnet, these elements are scarce and hard to come by.

The 30-year-old company says it has a unique history in its ability to process and separate heavy rare earths. That’s because the precursor to Neo Performance Materials is none other than Magnequench. In fact, it retains the Magnequench brand and website.

We know that by 2001, Magnequench’s US production facilities were relocated to China. In 2005, Magnequench merged with Canada-based AMR Technologies. Archibald Cox was listed as the largest shareholder on the board of directors. In 2006, AMR Technologies changed its name to Neo Material Technologies (NEM).

NEM was acquired in 2012 by Molycorp, the former owner of the Mountain Pass rare earths mine, that until recently, mined light rare earth elements from its California operation and shipped them to China for processing, through an agreement between current Mountain Pass owner MP Materials and Shenghe Resources of China. It now processes light rare earths at its facility in Texas.

The International Centre for Defense and Security tells us that as of 2022, NPM’s largest shareholder was Hastings Technology Metals Ltd., an Australian rare earths developer. Wyloo Metals, also from Australia, owned by investment fund Tattarang, funded Hastings for the acquisition of NPM. And here is the Chinese connection, which 30 years after the Magnequench sale, remains at the core of Neo Performance Materials, supposedly the West’s great hope in developing rare earths magnet technology outside of China and touted by Western leaders at this year’s G7 summit:

Tattarang’s owners have personally reaped significant financial benefits through Fortescue Metals Group, selling iron ore to China, which still accounts for as much as 88% of Fortescue’s revenue. Other evidence — documented in this analysis — points to ties between Tattarang’s ownership and PRC political influence operations. NPM is similarly dependent on the Chinese market, from which it derives approximately 32% of its revenue. In addition, research shows that NPM has four production facilities located in China.

According to the Heritage Foundation, Neo Performance Materials and its Magnequench affiliate report that 85% of their manufacturing facilities are in China (the other 15% is in Thailand); that 95% of their personnel are located in China; and that all of their China manufacturing facilities are in the form of joint ventures with Chinese state-owned enterprises.

Clinton and CFIUS culpable

In 2008, while campaigning for president against Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton stated that, while the sale of Magnequench happened in 1995, there were assurances that production would stay in the US, and that the subsequent George Bush administration failed to act when the jobs and production eventually left Indiana.

“A Chinese company bought Magnequench,” she said in a speech in Pittsburgh. “The people of Indiana, the company and the elected officials begged the Bush administration to block the Chinese company from moving the jobs to China…. Not only did the jobs go to China, but so did the intellectual property and the technological know-how to make those magnets…. I’m not comfortable with the fact that we now have to buy magnets for our bombs from China.”

In reality, the Magnequench saga dates back to the Bill Clinton administration, so Hillary Clinton’s finger should have been pointed at her husband, not Dubya.

The Heritage Foundation agrees that Magnequench’s story is indeed a story of executive branch disregard for the health of the nation’s defense industrial base, but the Administration of Bill Clinton bears culpability for letting it happen in the first place.

Magnequench, says the Foundation, had a unique expertise in the manufacture of high-powered neodymium magnets, which it pioneered in the 1980s for its parent company, General Motors, to use in vehicle airbags and mechanical sensors.

The company also provided critical component parts to “precision-guided munitions” (PGM) that were then in great demand by the DoD. Magnequench reportedly supplied 85% of the neodymium magnets used in motors for PGMs.

As importantly, neodymium magnets are the reason why high-speed, high-capacity computer data storage devices work, which is why they are found in literally ever computer, worldwide.

All of which creates an air of mystery over why Magnequench was allowed to be sold in the mid-1990s. The details are as follows:

- When GM put Magnequench up for sale in 1995, an investment consortium headed by Archibald Cox Jr., the son of the Watergate prosecutor of the same name, came up with the $56 million asking price. The consortium was called The Sextant Group, and as stated above, it was a front for two Chinese companies, state-owned metals firms San Huan New Material and China National NonFerrous Metals Import and Export Company. In the deal, the two Chinese firms reportedly took at least 62% of Magnequench’s shares. Cox was appointed CEO.

- The chairman of San Huan, Zhang Hong, was the son-in-law of former Chinese President Deng Xiaoping. He became chairman of Magnequench. The Heritage Foundation notes that Zhang’s desire to acquire Magnequench was informed by the Chinese government’s and his father-in-law’s “Super 863 Program” to develop and acquire cutting-edge technologies for military applications, including “exotic materials”. The other Chinese investor in Magnequench, CNNMIEC, was at the time run by another Deng Xiaoping son-in-law.

- One would think that the sale at the time for $56 million of a small company controlling advanced technology designed for both military and commercial uses to an entity controlled by two Chinese companies would have created serious concerns and a corresponding special investigation by then-President Bill Clinton, who was in the White House from 1992-2000.

- The Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States (CFIUS) might not have approved the purchase if the Chinese companies’ involvement had been fully transparent, highlighting the perception that The Sextant Group provided a cover for the acquisition. (AI Overview)

- The U.S. State Department overruled Pentagon concerns, and the sale went through with a promise to keep production in the US for at least a decade. This promise was not kept, and by 2004, the last US Magnequench facility closed, with equipment and production moved to China. One Magnequench employee said, “I believe the Chinese entity wanted to shut the plant down from the beginning. They are rapidly pursuing this technology.”

- Cox maintained that the Valparaiso, Indiana, plant closed because it was losing money and that the technology involved was not a secret, as the rare earths were Chinese and the technology was Japanese.

Why didn’t Clinton block the transaction? As president, Clinton, through a 1988 federal law, had been granted the power to block any financial transaction made between an American and a foreign-owned company, were it determined that “there is credible evidence that leads the President to believe that the foreign interest exercising control might take action that threatens to impair national security.” Clinton apparently did not find such “credible evidence.” Or to be more precise, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), a federal agency that had been established under the Reagan Administration to review such complex transactions, found no such evidence. So, with the stamp of approval of the CFUIS (The agency is comprised of 12 members representing major departments and agencies within the federal Executive Branch), the sale went through in 1995. (Gazette)

That same year, the Clinton administration shut down the US Bureau of Mines, which had been researching and developing energy sources including light rare earths and heavy rare earths.

The head of CFIUS at the time was Secretary of State Robert Rubin. Rubin’s role as a China sympathizer becomes apparent when we look at his record in office. As Treasury Secretary, Rubin helped negotiate China’s entry into the World Trade Organization. As co-chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations, he participated in the China-U.S. Track Two High-Level Dialogue to improve bilateral relations (AI Overview).

Bill Clinton’s position on China centered on a policy of “constructive engagement,” which aimed to integrate China into the international community and global economy in the belief that economic openness would foster political freedom and stability. (AI Overview).

Still, it’s remarkable that, even as The Sexton Group began shutting down the Magnequench plant in Indiana and transferring operations to a factory in China, President Clinton remained silent.

Clinton’s final means of assisting China at the expense of the United States came in October 2000, when he signed the China Trade Bill into law. Under the bill, China was granted even greater access to US technology, including technology related to LREEs, HREEs and permanent magnets — by which time China had attained 80% global control of all three.

Shuttering Mountain Pass

In 1998, the Clinton administration was instrumental in the closing of America’s only rare earths mine, Mountain Pass. Claiming that the mine’s existence threatened an endangered species, the Desert Tortoise, Clinton asked the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) to take legal action against it.

A key event in the mine’s 2002 demise was having to pay over $1.4 million in fines and settlements for repeated spills from a pipeline used to transport wastewater to evaporation ponds.

The wastewater contained heavy metals and radioactive components, specifically naturally occurring thorium and radium from the rare-earth ore processing. In total, approximately 600,000 gallons of hazardous waste flowed onto the Mojave Desert floor. (AI Overview)

In 2010, an international incident sent rare earth oxide prices into the stratosphere. A Japanese naval vessel interdicted a Chinese fishing boat near the Senkaku Islands, which Japan and China both claim ownership of, and detained the captain. The Chinese decided to ban all rare earth exports to Japan, then an industrial powerhouse and China’s largest REE customer. The rare earths market panicked, and within months, all of the rare earth oxides gained in price.

The result was the re-opening of the Mountain Pass mine, including a $130 million investment by Japanese conglomerate Sumitomo to upgrade the mine. By 2014 it was producing 4,700 tons of rare earths a year.

While the spike in rare earths prices was good for miners like Molycorp and the numerous exploration companies that sprang up in search for them, buyers of products made from rare earths balked and pressured governments to do something about it. The US, European Union and Japan brought a case to the World Trade Organization to try and settle the dispute and get China to lift the restrictions.

In 2015 it did, resulting in a torrent of Chinese rare earth exports into the market and the inevitable collapse in prices. The move caught Molycorp off-guard. The company had just spent over a billion dollars on another upgrade at Mountain Pass but within months, the company fell deeply in debt and went bankrupt.

The mine was put on care and maintenance and eventually sold at auction in the summer of 2017 for a shocking $20.5 million – a fraction of its previous worth — to MP Materials.

Re-opening it, but with a catch

The mine re-started operations in January 2018.

Up until recently, MP Materials dug up predominantly light rare earth elements from Mountain Pass and sent them to China for processing — leading to accusations that the company was “owned” by China and did nothing to transform the United States from a rare earth’s miner to a rare earth’s refiner and permanent magnets producer.

Shenghe Resources, a Chinese company with partial state ownership, holds an 8% stake. Shenghe was the company doing the processing; however this stopped in April 2025, when MP Materials stopped shipping rare earths concentrate to China following China’s imposition of rare earths export controls and retaliatory tariffs.

In January 2025 the company announced it commenced commercial production of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) metal and trial production of automotive-grade, sintered neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets at its Independence facility in Fort Worth, Texas.

MP has ramped up its capacity to produce rare earth concentrate from its Mountain Pass mine, which it turns into neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) metal magnets at Independence.

But it’s the NdFeB magnets that are important.

According to the company, they are “the world’s most powerful and efficient permanent magnets — essential components in vehicles, drones, robotics, electronics, and aerospace and defense systems.”

The Independence facility is expected to produce about 1,000 tonnes of NdFeB magnets per year, with a gradual production ramp beginning in late 2025. The facility will supply magnets to General Motors and other manufacturers, sourcing its raw materials from Mountain Pass.

While MP Materials expects to produce 1,000 tonnes of NdFeB magnets, by contrast, China produced an estimated 300,000 tonnes of NdFeB magnets in 2024, up from 280,000 tonnes in 2023.

1,000 tonnes vs 300,000 tonnes means MP Materials only has the capacity to supply 0.003% of China’s NdFeB magnet capacity.

It’s also the kind of rare earths that Mountain Pass is producing that is important. While the open-pit mine last year produced a record-high 45,000 tonne of rare earth oxides in concentrate, and a midstream production record of about 1,300 tonnes of NdPr oxide (needed for the magnets), MP Materials produces virtually no rare earths needed for defense applications.

The Mountain Pass mine primarily produces neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) oxide, a key component in NdFeB permanent magnets. Other rare earth compounds include lanthanum carbonate and cerium chloride, as well as bastnaesite concentrate and heavy rare earths concentrate. The latter, as far as I can tell, has yet to be incorporated into the Independence permanent magnet facility.

Need for heavies

The light rare earth elements are the easiest to extract and separate, whereas heavy rare earths separation is complicated, expensive, and messy, creating environmental degradation unless stringent regulations are put in place.

Yet it is the heavies that are most needed for high-tech and military applications. The rare earth element samarium and the critical metal cobalt create samarium-cobalt permanent magnets that are valued for their resistance to high temperatures and corrosion.

Defense contractor Lockheed Martin is the main US consumer of samarium, with about 50 pounds of samarium-cobalt magnets in an F-35 fighter plane. The magnets retain their magnetic properties under temperatures high enough to liquefy lead.

Currently, there is no heavy rare earth separation capacity in the United States, though efforts to build this capability are underway.

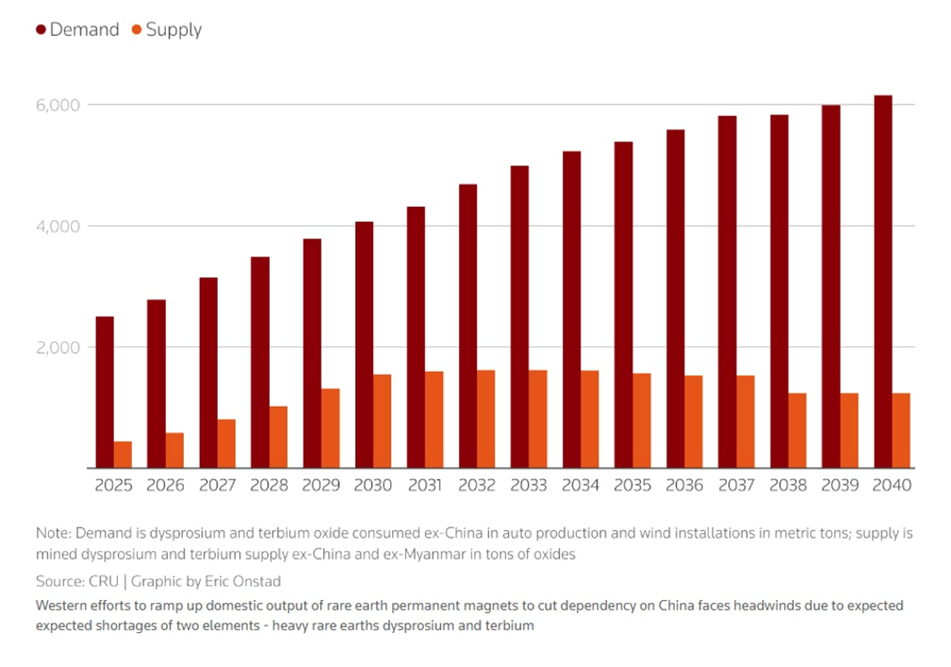

Analysts quoted by Reuters say that heavy elements dysprosium and terbium could be an Achilles heel for MP Materials and the West’s campaign to forge a magnets industry away from China.

“MP Materials may have a formidable challenge,” said Ilya Epikhin, senior principal with consultants Arthur D. Little. “They’ll need to go to Brazil or Malaysia, or some African states to find those resources, but it can take a lot of time.”

As mentioned, MP Materials has scant heavies.

The company according to Reuters aims to eventually lift magnet output to 10,000 tonnes a year and plans to launch a heavy rare earths separation facility next year that will produce 200 tons a year of dysprosium and terbium.

Remember, dysprosium and terbium are heavy rare earths that when added to NdFeB magnets, allow them to tolerate the super-high temperatures required in military applications.

The problem as stated above is Mountain Pass. The mine mainly produces light rare earths; the deposit contains less than 1.8% medium and heavy REEs. While it has stockpiled several hundred tons of medium and heavy rare earth concentrate for magnet production, this only contains 4% dysprosium and terbium.

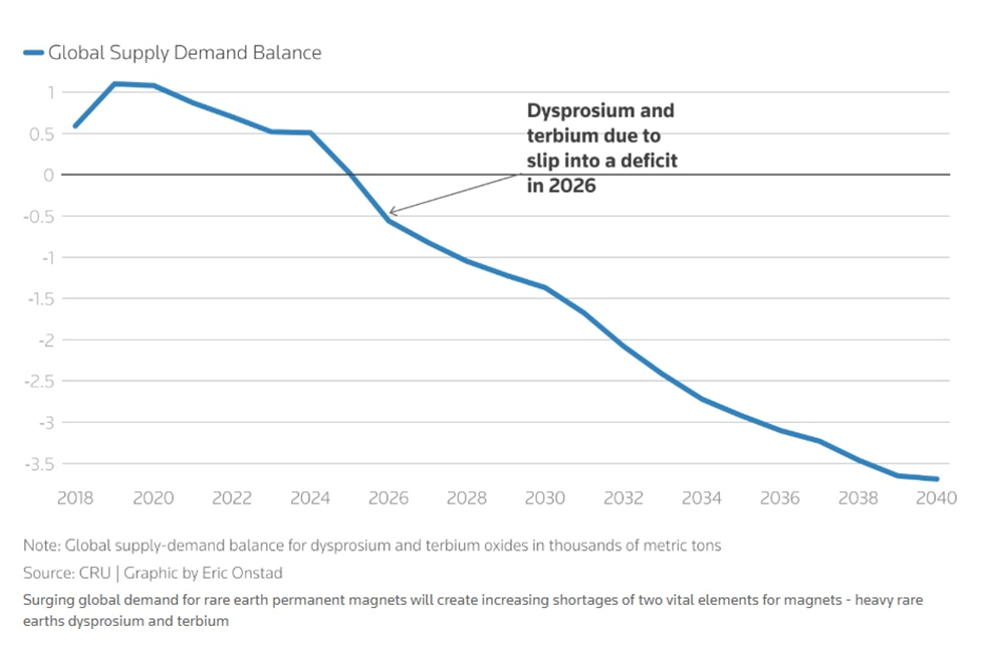

Mines outside of China are forecast to meet only 29% of the heavy rare earths consumed outside China in the auto and wind sectors by 2035.

The scarcity of dysprosium oxide outside China has raised the price in Rotterdam to $900 per kilogram, more than triple the price in China of $255, according to data provider Fastmarkets.

“If you talk about critical resources, it’s really the heavies, the heavies, the heavies — all the rest we will get,” said Erik Eschen, CEO of Germany’s Vacuumschmelze (VAC), one of the few rare earth magnet producers outside China.

Commodities Research Unit (CRU) forecasts a global deficit by 2035 of 2,920 tons of dysprosium and terbium oxides — despite efforts by Lynas Rare Earths and Iluka Resources to separate heavy rare earths using HREE feedstock from mines in Australia.

MP Materials and Lynas, whose refinery is in Malaysia, are both looking for additional ore to process since their own mines are not rich enough in heavy elements.

Consequences

Following the Magnequench debacle, the Chinese filled the void left by US rare earth mining with gusto — establishing the world’s largest rare earth research facility; filing the first rare earth patent in 1983, and over the next 14 years filing more patents than the US which had been working on them since 1950; and acquiring US technology in metals, alloys, magnets and rare earth components.

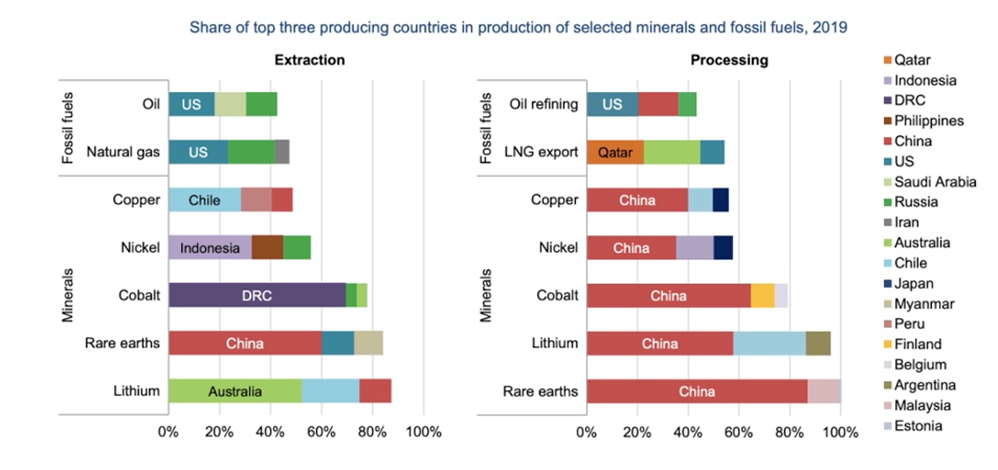

As of 2023, China accounts for around 69% of the world rare earths production. The United States is far behind at 12%, followed by Burma and Australia at a respective 11% and 5%.

It’s easy enough to dig up rare earths; the expertise comes in separating, purifying and refining them.

China is the only country that carries out all these stages, with Australia and the United States selling some of their semi-processed ores back to China to complete the refining! China thus produces 85% of the purified light rare earths used worldwide, and 100% of the heavy rare earths. (Polytechnique Insights)

Source: IEA

In fact, China has a monopoly on the entire rare earths value chain. But the country has progressively moved from extraction to separation, to the manufacture of magnets.

In 2021, China further consolidated its rare earth industry by establishing China Rare Earth Group Co. Ltd, a state-owned enterprise that is a conglomerate of top industry producers to increase its pricing power and production efficiency.

According to the Heritage Foundation,

“…when one considers that virtually no piece of advanced information technology can be fabricated without rare-earth oxides-which, of course, means that no weapons system can be assembled without them.”

The bottleneck is not in the mining but the processing of rare earths. Techspot notes that “it is the industrial circuitry that converts ore and scrap into high-purity oxides and finished magnets… While the term “rare earth” implies scarcity, the more consequential constraint is a refining and processing system dominated by China.”

Indeed, separating and extracting a single REE takes a great deal of time, effort and expertise. For more read the section on ‘Rare earths 101’ in this 2018 article by AOTH

Rare earths used in defense

Rare earth elements are present almost everywhere in weapons systems. For example, an American F-35 fighter plane contains more than 400 kg of various materials containing at least one rare earth.

Magnets made from Chinese rare earths are also used in the Joint Strike Fighter, the Pentagon’s answer to a one-size-fits-all warplane.

Without rare earths mined and processed in China, America would be unable to manufacture military hardware. The statement “America cannot build a single guided missile without permission from Beijing” is 100% correct.

Civilian uses of rare earths would also be put in jeopardy. This includes rare earth elements incorporated into electric vehicle motors, computer chips, fiber-optic cables, flat-screen televisions, wind power turbines and nuclear power, just to name a few uses. Click here for a more comprehensive list

Rare earths are great multipliers; they are used in making everything from computer monitors and permanent magnets to lasers, guidance control systems and jet engines. There are no substitutes.

While relatively small by market volume REE’s are terrific market multipliers – rare earths have an outsized influence as critical components in strategic industries such as electric vehicles, renewable energy, and of course, defense.

The global rare earth elements market size was approximately $3.39 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach over $8.14 billion by 2032, driven primarily by the magnets segment. The value of rare earth oxides consumed in energy-transition applications alone is forecast to rise from $3.8 billion in 2022 to over $36 billion by 2035. (AI Overview)

The $392-billion F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter program was close to being canceled but for intervention by the Pentagon to prevent further delays. Reuters reported in 2014 that the chief US arms buyer allowed two F-35 suppliers, Northrop Grumman Corp and Honeywell, to use Chinese magnets for the plane’s radar system, landing gears and other hardware.

In doing so, the Pentagon was actually waiving laws banning Chinese-built components on US weapons.

The US military is an important buyer of permanent magnets. Stealth helicopters have neodymium magnets in their noise cancellation technology blades.

Aircraft use them in their electric motors and actuators, as do hub-mounted electric traction drives and integrated starter generators. Aircraft electrical systems employ samarium cobalt permanent magnets to generate power.

Rare earths in the cross-hairs of new high-tech arms race

But it’s all about the missiles

It was previously stated that it was believed China targeted Magnequench for obtaining the technology to develop its long-range cruise missiles; magnets were, and still are, the basis of China’s missile program.

The Chinese military is literally making thousands of missiles a month and are doing it to protect themselves against their main adversary, the United States. It’s also why China is refusing to allow the export of magnets used in military applications to the United States.

On June 11, US and Chinese officials finalized a new trade framework following two days of negotiations in London. According to the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), the agreement includes a commitment from Beijing to resume exports of rare earth elements and magnets to the United States, following two months of severe export restrictions that disrupted key inputs for the automotive, robotics, and defense sectors.

In early April, China imposed export controls on seven rare earth elements (REEs) and related permanent magnets, citing national security concerns and in response to US tariffs. The targeted REEs included samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium and yttrium.

The delay in issuing export licenses has had a significant impact on US, European and Japanese companies, particularly auto manufacturers.

According to CSIS, Ford shut down production of the Ford Explorer at its Chicago plant for a week in May due to a rare earth’s shortage; several European auto supplier plants and production lines were closed; Nissan and Suzuki Motors reported supply disruptions; and shipments of rare earth magnets to Germany fell 50% from March to April.

Notably, China has weaponized various minerals over the past two years, including restrictions on gallium, germanium, graphite, antimony, tungsten and rare earths.

While China promised to fast-track approval of REE export applications, the applications are from non-military US manufacturers, and the licenses only have a six-month term. In other words, the United States is not getting any rare earths from China for defense purposes, and the rare earth export licenses for civilian purposes are temporary; they have to be renewed every six months.

According to MSN, the Defense Department relies on magnets for missiles, drones and jet fighters. However, it doesn’t buy enough magnets to sustain a full plant, so it has historically relied on magnet suppliers from Japan and Europe, which in turn rely, in part, on Chinese raw materials.

Anti-ballistic missiles like Israel’s “Iron Dome” use samarium-cobalt and neodymium magnets for various functions within the missile’s guidance and control systems. It was reported that Israel and the United States used ballistic missile interceptors at a rapid clip after four days with Iran.

There are even concerns that a direct US strike on Iran could lead to bigger Iranian retaliation against Israel that would drain the US’s global stockpile of missile interceptors to a “horrendous” level, one US official said.

China’s idea, imo, is to send Iran enough material to make so many missiles they can lob 2,000 missiles at Israel in a wave, followed by more waves of the same size.

It’s scary to think how quickly this could escalate into a nuclear war once Israel’s conventional missiles run out.

Beijing is reportedly seeking to rebuild Iran’s missile program after Israel attacked its missile and nuclear facilities during the 12-day war in June. On Oct. 31, Newsweek reported that Iran has received from China 2,000 tons of sodium percholate, a missile fuel precursor, enough for 500 ballistic missiles.

Also, an August report from Israeli media warned of increased military cooperation between Iran and China in the production of surface-to-surface missiles.

China is supplying not only Iran, but Russia with weaponry, the latter indirectly. China is also buying Russian oil, sanctioned by the West. From the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission:

According to a report, several Chinese companies with ties to the Chinese government are supplying Russia with gallium, germanium, and antimony, critical minerals that are used to produce drones and missiles for Russia’s war in Ukraine. China banned the export of these same minerals to the United States in December 2024, citing their military applications.

There’s a reason why China took over the rare earths, and there’s a reason why they’re not giving the US military anything. China has a window right now where they have the upper hand in missiles, and they will for the next 10-15 years, until the United States can develop its own rare earths supply chain that doesn’t rely on China for the magnets needed to make missiles.

Beijing doesn’t want the US to catch up and has made this apparent by denying it the rare earths needed for defense, especially the magnets required for missile manufacturing.

The US still doesn’t have the heavy rare earths, at least not in the quantifies needed. They still don’t have the smelting and the refining technology. And they don’t know how to make the magnets that they need to make missiles.

Companies such as General Electric, Northrup Grumman and Boeing lack the capability to process REE oxides into usable components. Currently, almost all REEs mined outside of China are shipped there for processing into high-value metals, magnets and alloys. (Supply Chain Brain)

Conclusion

It’s incomprehensible that the United States lumbered into a position of near utter dependency on China for rare earth metals — ceding its monopoly to China either through ignorance of the importance of rare earths or allowing itself to become a victim of subterfuge when it let Magnequench go to a company with close ties to former Chinese President Deng Xiaoping.

We may never know who was asleep at the wheel, but we do know that the situation as it stands is untenable and must be corrected.

President Trump has made rare earths a priority through various executive orders in his first and second terms. The US government has taken a 15% stake in MP Materials through a $400 million investment from the Department of Defense.

MP Materials has started refining rare earths at home rather than sending them to China. The other big non-Chinese rare earths company, Lynas, continues to refine REEs in Malaysia. The quest for heavy rare earths separation capability has started but remains elusive.

China has a lock on rare earths refining and has the capability, and willingness, to weaponize the 17 elements.

Just weeks after the April restrictions took effect, multiple defense suppliers — including subcontractors for radar and propulsion systems — reported slowdowns and sourcing complications, according to Modern War Institute.

Ford was forced to shut down production for a week. German automakers warned of production lines coming to a standstill, writes blogger Michael Dunne, adding that “The message was abrupt and unmistakable: China holds the supply chain equivalent of nuclear weapons. Without magnets, American and European cars do not get built.”

In the 1980s, the United States dominated the global rare earths industry, epicentered at its Mountain Pass mine in California. General Motors’ Magnequench pioneered magnet manufacturing. As Dunne notes, “The United States controlled both the raw materials and the cutting-edge technology.”

Then came the Magnequench saga.

Either through naivety, ignorance or subterfuge, the Clinton administration and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States allowed Magnequench to be sold to a small US company that served as a front for two Chinese companies whose chairmen had family ties to the very top of the Chinese Communist government’s power pyramid: former President Deng Xiaoping.

President Clinton had the power to quash the transaction, but he didn’t. As Magnequench’s facility in Indiana was dismantled and moved to China, Clinton was mute on the subject.

Since Magnequench, China’s rare earths ascent has been as remarkable for China as it has been devastating to the US.

In 1985 the US controlled 60% of rare earths production compared to China’s 30%. By 2024, China had achieved a virtual monopoly over the entire supply chain, from mining to processing to magnet manufacturing. China now makes 90% of the world’s neodymium magnets while the US produces 0.3%.

The United States can certainly try to catch up, but producing permanent magnets at scale will take up to 15 years. Again, the numbers are stupid. China produces 300,000 tonnes of NdFeB magnets annually. US capacity is projected to reach barely 6,000 tonnes by 2027, less than 2% of Chinese output.

China has a chokehold on most critical minerals including rare earths and can exert pressure any time it feels like it. After China imposed export restrictions on seven rare earths in April 2025, Chinese rare earth magnet exports halved from April to May. Dunne notes German automakers, who are the largest importers, saw shipments reduced by 50%. American defense contractors faced potential shutdowns for weapons systems.

The recently reached US-China trade deal keeps in place restrictions on military-grade magnets and imposed six-month licensing caps to maintain leverage. (The Dunne Insights Newsletter)

China is seeking to distance itself further from the West by forming a rare earths alliance with developing nations.

Of course, we have to recognize that Magnequench was a different time in Sino-US relations. China, intent on shifting its agrarian economy to a manufacturing-driven export economy, was building factories, public buildings and residential complexes that all required offshore minerals like copper and iron ore, along with copious oil and gas, and coking coal to feed its steel mills and thermal coal to run its power plants.

In 2010 China was invited to become part of the World Trade Organization. Suddenly, Communist China with ties to US Cold War nemesis Russia was a free-trading friend.

Tourism and cross-cultural links between China and the West blossomed. This was before China started building up its military, began patrolling the South China Sea along with building artificial islands that house military infrastructure, and belligerently calling for the re-unification of Taiwan, a US ally.

It was before Chinese interference in elections and the emergence of Huawei as a Trojan horse for Chinese technology to infiltrate Western telecommunications systems. And it was before the first trade war between China and the United States that started in 2018, and the second trade war we are currently in.

Arguably, should the same situation come about nowadays, Archibald Cox Jr. would, imo, be charged with treason and there would be a better reason than Monica Lewinsky for Bill Clinton to be impeached.

Subscribe to AOTH’s free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

MORE or "UNCATEGORIZED"

Eldorado Announces Strong Exploration Results of Multiple New High-Grade Zones in Canada and Greece and Increases 2026 Exploration Investment, Reinforcing Confidence in Discovery Strategy

Eldorado Gold Corporation (TSX: ELD) (NYSE: EGO) is pleased to announce the discovery of four new hi... READ MORE

First Atlantic Nickel Increases RPM Zone Strike Length 50% to Over 1.2 km and Width to Over 800 m from Phase 2x Drilling at Pipestone XL Magnetic Nickel-Cobalt Alloy Project

First Atlantic Nickel Corp. (TSX-V: FAN) (OTCQB: FANCF) (FSE: P21) is pleased to announce pos... READ MORE

McEwen Drilling Returns Significant Intersection at Gold Bar Mine Complex in Nevada: 5.55 gpt Gold over 44.2 Meters; Transformation into a Long-Life Mine Continues

McEwen Inc. (NYSE: MUX) (TSX: MUX) announces new drill results from the Gold Bar Mine Complex in th... READ MORE

Aya Gold & Silver Provides 2026 Outlook and Strategic Priorities

Aya Gold & Silver Inc. (TSX: AYA) (OTCQX: AYASF) is pleased to provide its 2026 outlook and pres... READ MORE

Highlander Silver Announces US$40 Million Strategic Investment by Eric Sprott to Accelerate Growth

Highlander Silver Corp. (TSX: HSLV) is pleased to announce that Mr. Eric Sprott, an arm’s l... READ MORE