Rick Mills – “Debt and What Will Cause the Next Financial Crisis”

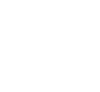

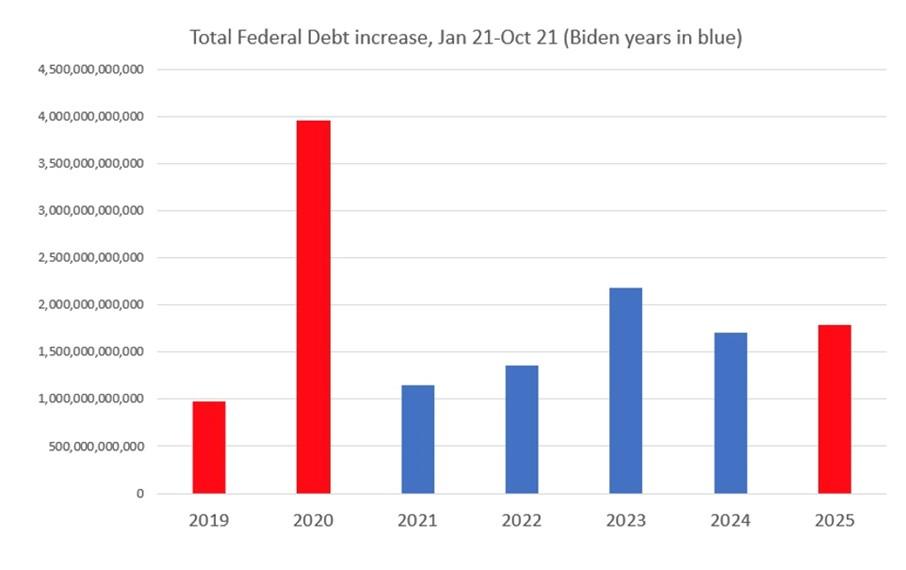

It took just 71 days for the US federal government to add another trillion dollars to the national debt.

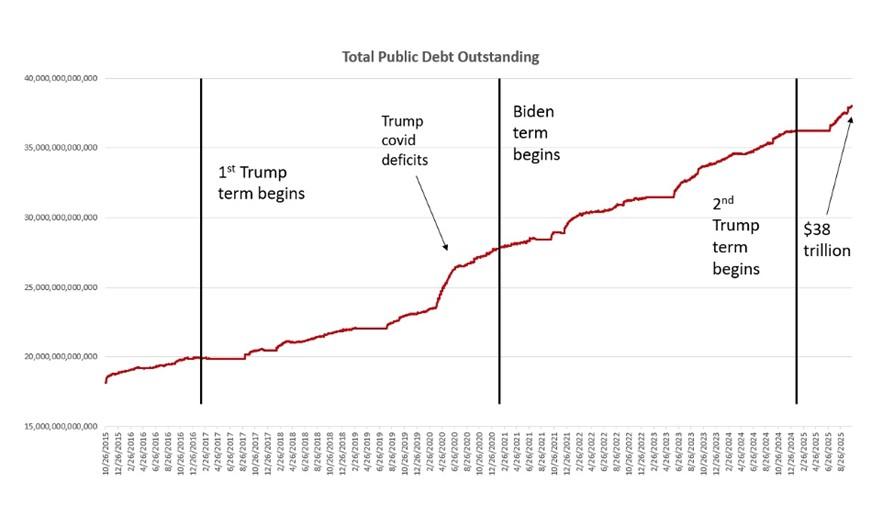

In August, the debt soared past $37 trillion for the first time. On Oct. 21, it blew past $38 trillion, according to FXStreet.

Source: FRED

This happened despite tariff revenue and Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) staff reductions. And US debt is accelerating.

In 2020, the Congressional Budget Office projected the debt wouldn’t hit $37T until 2030. Five year earlier, we’re well past that.

Putting the growth in context, the national debt hit $34 trillion in January 2024 and $35 trillion in November 2024.

It took 188 days for the debt to grow from $35 trillion to $36 trillion. It took another 265 days to reach $37 trillion. But don’t be fooled. The borrowing didn’t slow down between $36 and $37 trillion. It was just that the federal government ran up against the debt ceiling on January 1. As a result, it couldn’t borrow any money until the enactment of the “Big Beautiful Bill,” which raised the debt ceiling by $5 trillion as of July 1.

At that time, the national debt stood at $36.2 trillion. It took less than two months for the federal government to borrow more than $800 billion, pushing the debt over $37 trillion.

And here, barely two months later, at $38 trillion.

It won’t be long before we’re talking about a $39 trillion national debt.

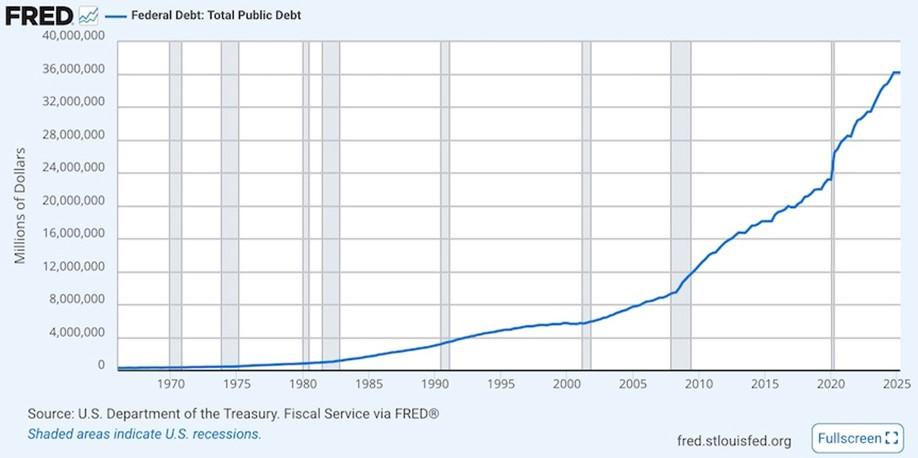

What does $38 trillion even mean? First, it’s more than the annual GDP of China, India, Germany, Japan and the UK combined.

Second, to pay off this debt, every US citizen would have to cut a check for $110,641.

Third, because so many Americans don’t pay taxes, the burden on regular, law-abiding taxpayers is much greater. To pay off the $38T would require each taxpayer to write a check for $327,707.

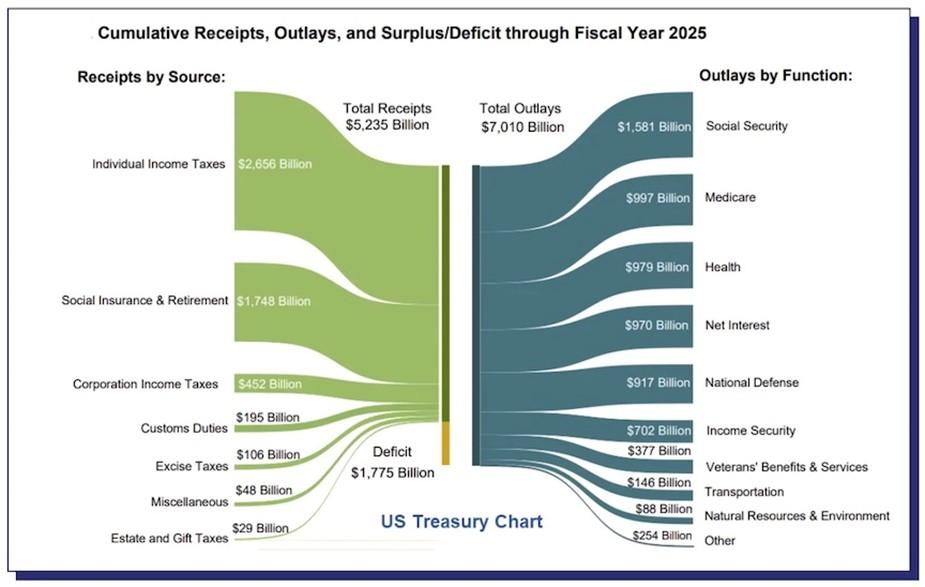

Again, this is despite the Trump tariffs and how much they were supposed to pad government revenue. Tariffs receipts grew by 142% in 2025 but that wasn’t anywhere near enough to fill the deficit hole. Despite a 6.4% increase in federal revenue in fiscal 2025 and an 11% increase the previous year, the US government still ran the fourth-largest budget deficit in history. These numbers are from FXStreet.com.

The problem, they conclude, isn’t that there is a lack of tariff revenue or that taxes are too low. It’s an overexuberance of spending. For proof, consider that the US government spent over $7 trillion in fiscal 2025, a 4.1% increase over fiscal 2024.

What’s the big deal behind this ever-expanding debt pile, not only in the US but globally, as we shall see below?

The first thing is that a large national debt puts a drag on economic growth. FXStreet cites the national debt clock’s figure of debt representing 120.6% of GDP. Studies have shown that a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 90% slows economic growth by about 30%.

Source: usdebtclock.org

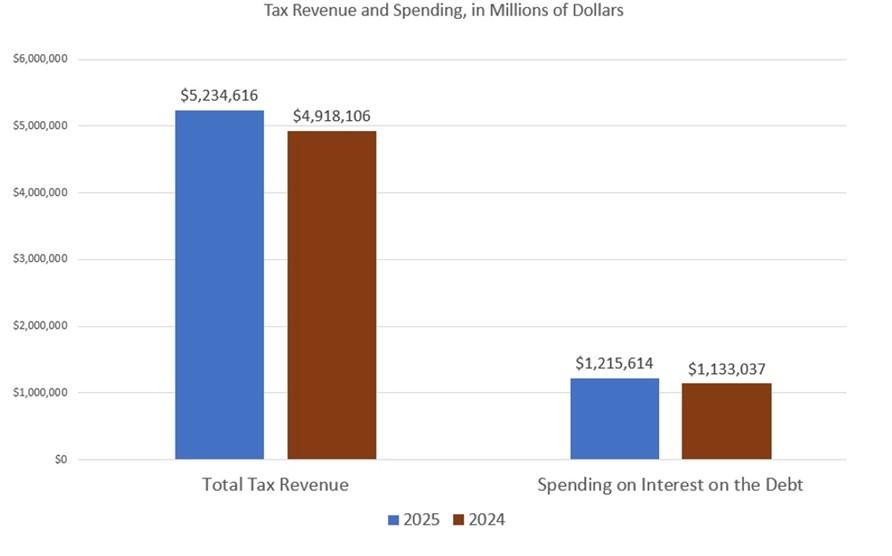

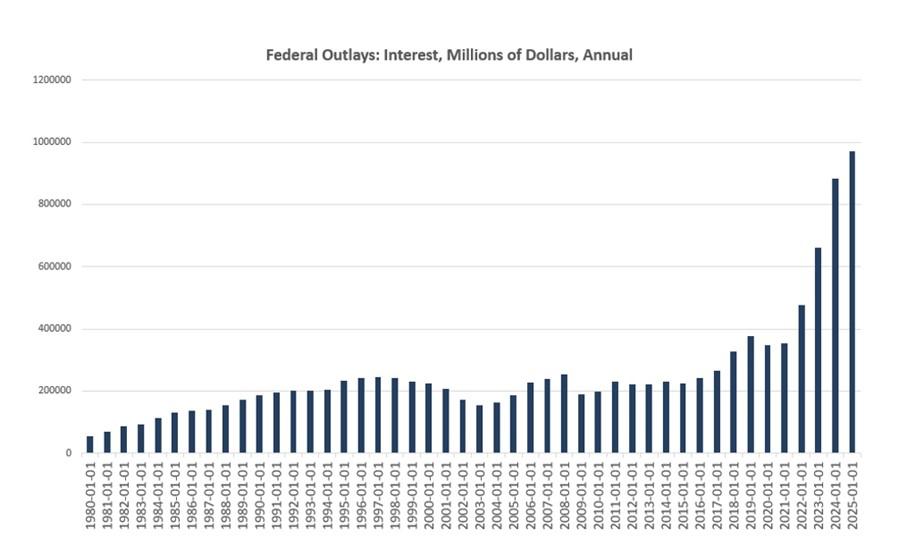

A high debt also turns the screws tighter on governments that have to pay interest on it. In fiscal 2024, interest on the national debt cost $1.2 trillion, up 7.3% over the previous year.

Well, so what? The figure is more impactful if one appreciates that in the last fiscal year, the US government spent more on debt interest than it did on national defense ($917 billion) or Medicare ($997B). Only Social Security was higher at $1.58 trillion.

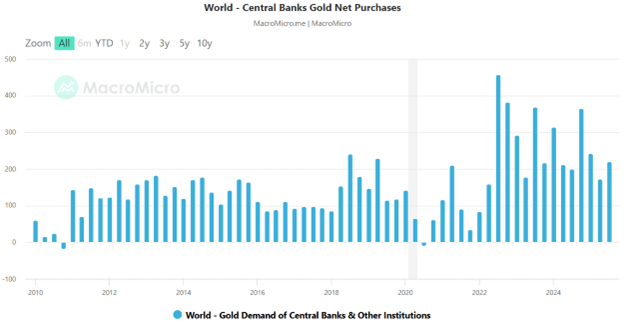

At AOTH, we have previously pointed out that at some point, the world will decide it’s no longer interested in financing the US government’s borrowing and spending. In fact, this is already happening, concurrent with the de-dollarization trend and central bank gold buying.

Central banks now hold more gold than US Treasuries

FXStreet states:

As the Bipartisan Policy Center points out, the growing national debt and the mounting fiscal irresponsibility undermine the dollar.

“Confidence in U.S. creditworthiness may be undermined by a rapidly deteriorating fiscal situation, an increasing concern with federal debt set to grow substantially in the coming years.”

And then there’s this:

If you’re wondering why the Federal Reserve is talking about easing monetary policy despite persistently high inflation, look no further than the debt. The government needs the central bank to keep its thumb on the bond market. That requires it to hold more Treasuries on its balance sheet, thereby creating demand for bonds. This allows the federal government to borrow at a lower interest rate than it otherwise would. This is exactly why Fed Chair Jerome Powell recently said balance sheet reduction will end soon.

Given the budget deficit and the pace of debt accumulation, it may not be long before the Fed returns to quantitative easing (QE).

And that means even more inflation.

In this article we are taking a deep dive into the growing US and global debt bubble, and what it means. Politicians no longer seem to care so why should you? Read on to find out what’s coming down the pipe.

The US debt problem

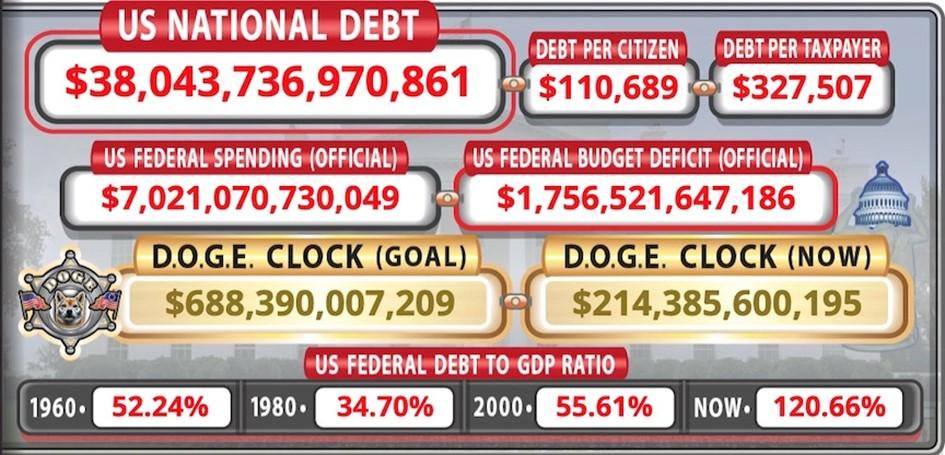

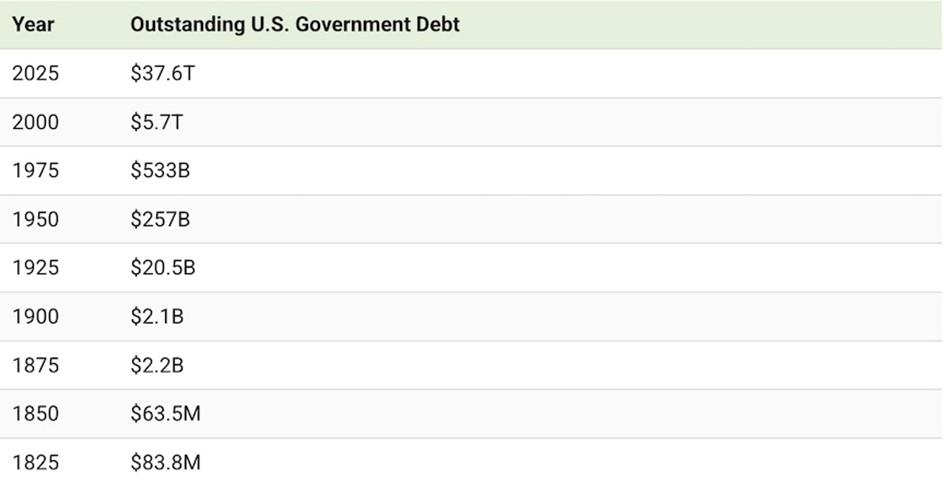

Let’s start by shining a spotlight on the alarming increase in the US national debt. Visual Capitalist put out a good infographic. Among the key takeaways are that US debt now stands at $37.6 trillion, or 125% of GDP. Net interest payments on the debt are set to reach $1.3 trillion by 2030 and $1.8T by 2035. At that point, interest payments on the debt would be 22.2% of federal revenues.

This year, interest costs are forecast to reach $952 billion; over five years they have nearly tripled.

The accompanying table shows the debt has swelled nearly 7-fold in 25 years, largely driven by the federal government’s largesse during the financial crisis and the covid-19 pandemic. The infographics website points out that in 2020 alone, the Fed printed $3 trillion under quantitative easing.

Debt hasn’t always been a US problem. It actually fell from 106% of GDP in 1946 to just 23% in 1974. In 1835 under President Jackson the national debt dropped dramatically, from $4 million the previous year to a mere $34,000. Such numbers are inconceivable today.

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

The Economic Times of India points out that at current debt levels, the US government is borrowing $25 billion a day, and interest payments now exceed $1.2 trillion annually, more than defense. Importantly, the article says that Americans may soon feel the effects in taxes and social programs. Why?

If the government is spending more to service the debt, there is less money available to spend on social programs, things like education, health care, and infrastructure, which in America is decaying.

With debt to GDP at 125%, the country now owes more than it produces in a year. What is driving this higher ratio and why does it matter? As reported by The Economic Times:

Economists warn that a rising debt-to-GDP ratio can slow economic growth and raise borrowing costs.

Several factors are driving this surge in debt. Budget deficits, rising spending on Social Security and Medicare, and tax policies that reduce federal revenue all contribute to the growing financial strain. Political gridlock has made it difficult to implement long-term solutions.

It all starts with the deficit. The debt is simply an accumulation of past and current deficits.

Eric Boehm of Reason points out that Donald Trump returned to the White House with a promise to slash spending by trillions and balance the federal budget. Neither has happened or will happen.

For the fiscal year ended on Sept. 30, the federal government spent a little more than $7 trillion and ran a $1.8T deficit. The $7T was a $310 billion increase from full-year 2024. The recipients were the usual suspects: Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid (representing a combined $245 billion). Spending on the Pentagon was $38 billion, and the Department of Veterans Affairs received $41 billion.

Remember, the Department of Defense budget does not count black ops, interest on the defense portion of the debt, and ongoing military obligations to veterans.

Other military expenses, such as military training, military aid and special operations, are put under other departments or are accounted for separately.

The DOD budget also doesn’t include the cost of overseas wars. That money is allocated to Overseas Contingency Operations.

The budget for nuclear weapons is split between the Defense Department and the Department of Energy.

If we include all the items not normally tallied under defense spending, and departments in which much of their spending is devoted to the military effort, we find that defense spending actually exceeds Social Security. Not only that but it’s also more than the expected budget deficits forecast for the next decade.

More guns than butter: US military spending to exceed annual deficits — Richard Mills

A few words about the controversial, now emasculated DOGE are a necessary part of this discussion. Eric Boehm writes:

Cutting silly government contracts and foreign aid might be a worthwhile effort, but that won’t make a dent in the budget deficit. Any serious effort at fiscal reform has to focus on the areas of the budget that are growing year over year—which, realistically, means looking at entitlement programs…

There are plenty of reasons to be skeptical that anything will change in the next three years. For one, Trump’s track record after nearly five years as president does not suggest he cares very much about actually cutting spending. The coming years will also bring greater headwinds to any attempts at reducing the deficit. That’s due in part to the expected increases in entitlement spending, as well as the fiscal effects of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which extended and expanded the 2017 tax cuts in ways that will likely add to the deficit.

Mike Shedlock of Mish Talk penned an article titled, ‘Zero Progress on the Reducing the Deficit Despite Tariff Revenue’. He noted this year’s deficit is similar to last year’s, despite an additional $118 billion of tariff revenue.

Other items to watch out for, that will have to be added to the $1.8 trillion borrowed in fiscal year 2025, include Obamacare subsidies, Trump’s “Golden Dome” defense shield, and whatever the mercurial president commits the United States to in Gaza, Afghanistan or Venezuela. Also, none of the long-term budget projections factor in the cost of a recession.

Source: Mish Talk

The high cost of tariffs

The Economic Times found that, although tariffs imposed by the Trump administration increased customs duties by 273% year on year, and brought in $21 billion in a single month, the windfall is not enough to offset the rapidly growing deficit.

In fact, tariffs come with costs the government never talks about.

A new study by S&P Global covered by Axios found that the tariffs will cost businesses more than $1.2 trillion this year, with most of that amount passed on to customers.

The data was collected from 15,000 analysts across 9,000 companies.

“Tariffs and trade barriers act as taxes on supply chains and divert cash to governments; logistics delays and freight costs compound the effect,” the researchers wrote in the report.

It also said that Trump’s suspension of the “de minimis rule”, which exempts packages valued under $800 from duties, increased the squeeze on companies.

Consumers could be impacted by Trump’s recent threat to ban imports of Chinese cooking oil, part of the spat between the two countries over soybean exports.

The Yale Budget Lab estimates that Trump’s latest tariffs will cost US households $2,400 this year, per Axios.

The IMF earlier this month warned that markets may be underestimating the risks from tariffs and rising debt.

The organization, via The Economic Times, revealed that global output is expected to ease from 3.3% in 2024 to 3.2% in 2025 and 3.1% in 2026, citing higher US tariffs which slow trade and investment.

The IMF also cautioned that for financial markets, risk valuations are now “well above fundamentals”, raising the possibility of sharp corrections.

(On Oct. 10 the Dow slid nearly 900 points after Trump threatened new tariffs on China, with the S&P500 and the Nasdaq closing sharply lower as US stocks booked a weekly loss — MarketWatch)

“Markets seem to have downplayed the potential effects of tariffs on growth and inflation,” the Fund said. Front-loaded consumption and investment are fading, and near-term global growth is starting to slow, particularly in the US.

Furthermore, debt continues to move toward governments, with expanding fiscal deficits pressuring sovereign bond markets.

Global debt

Debt strangulation is not, of course, merely a US phenomenon.

The IMF via Yahoo Finance warned on Oct. 15 that global government debt is on course to hit 100% of global GDP by 2029, which would be the highest since 1948, when the ratio was a record 132%. By 2030, government debt could soar to 123% of GDP (remember the US is already at 125%).

Among the G20 countries whose ratio is set to move above 100% in the coming years are the US, UK, China, France, Japan and Canada. The US is projected to surpass 140% of GDP by the end of the decade while China is on track to reach 113% by 2029. This in a country of savers.

Meanwhile, up to 55 countries whose ratios are below 60% are having trouble servicing their debts because interest rates have risen.

A Bloomberg editorial had this to say about ballooning global debt:

Public debt, to be clear, isn’t bad in itself, and there’s no fixed ceiling on how high it can safely go. But as it rises, so-called fiscal capacity shrinks, leaving governments less room to maneuver when the next crisis comes around. Eventually, a combination of protracted indiscipline, bad economic news and souring financial markets can dig countries into a hole so deep that the only way out is some form of debt default, either explicit or disguised by high inflation.

The editorial also notes that “times have changed” from the near zero percent borrowing rates of the pandemic period and before, but policymakers haven’t rolled back spending to pre-pandemic levels:

The facts have changed, but this mind-set persists. Most US policymakers have simply stopped caring about ever-rising debt. Elsewhere, governments might pay lip service to the need for discipline — in some cases adopting budget rules or creating “fiscal councils” to address the problem — but their actions have fallen short. If long-term inflation-adjusted interest rates outpace economic growth and drift even higher, debt will keep trending upward and deficits will be ever harder to cut.

What would be the consequences of global debt levels at 123%? According to Vitor Gaspar, head of the Fund’s fiscal affairs department,

“From our viewpoint, the most concerning situation would be one in which there would be financial turmoil.” More specifically, he warned of a possible “disorderly” market correction.

Despite edging up its 2025 global growth forecast, given a more benign impact from tariffs, the IMF was urging both advanced economies and developing countries to reduce their debt levels, cut deficits and build up buffers.

The Fund suggests that targeted public spending for education and infrastructure could boost GDP.

Economist Daniel Lacalle believes that “big government” created the current sovereign debt crisis. The end result of such voracious public spending without consequence is the rise of inflation and the appeal of gold, especially to central banks looking to hedge their risk of holding fiat currencies, which lose their value with time and government policies that debase them. In his words:

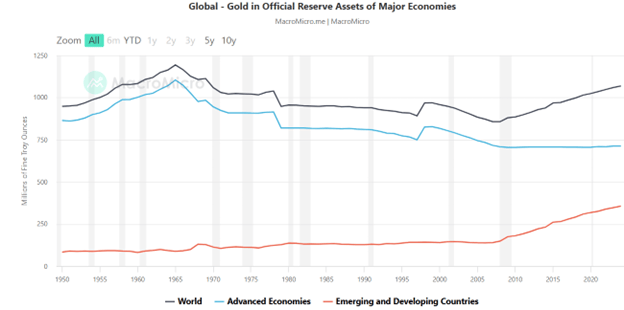

Developed economies’ governments of all colours, from Biden and Sunak to Macron and Ishiba, bought the MMT fallacy that “deficits do not matter” and “sovereign nations can issue all the debt they need without risk.” Virtually all international bodies hailed statism as the global solution. However, in 2022, global central banks and investors started abandoning sovereign debt as a reserve asset and decided to add gold.

Developed nations have surpassed the three limits of indebtedness: the economic, fiscal and inflationary limitations. When more public debt creates lower economic and productivity growth, the economic limit has been surpassed. When interest expenses and deficits continue to rise despite rate cuts and higher taxes, the fiscal limit collapses. Additionally, when governments become addicted to issuing more debt in any part of the cycle, with diminishing investor demand, inflation becomes persistent.

Another commentator, Hugo Dixon for Reuters, says Rich country debt will spur tax and price hikes.

Dixon believes that with government borrowing unsustainable in the United States and Europe, and with continued pressures to spend on climate, defence and aging populations, “some mixture of higher taxes and inflation will ultimately be unavoidable.”

He boils the problem down to one simple fact: governments are spending more than they are raising in taxes.

The best option would be to increase growth, but with tariffs still on the agenda, the more likely scenario is for rich countries to slow down.

Another option if to cut public spending. But there is always massive public resistance to this.

Another way to control mounting debt is so-called “financial repression”. This refers to policies that artificially suppress the interest rate that government bond holders receive. Also, deeply unpopular. Dixon notes this is only possible if a country restricts cross-border capital flows or if a country has a current account surplus — the latter not being the case for the US and Britain.

Defaulting on their debt is a last-ditch option that in reality is never going to happen to a G7 country.

That leaves two other ways to stabilize borrowing levels: higher taxes and inflation. “Both,” Dixon writes, “are extremely unpopular. But the United States, Britain and France will ultimately be driven to some mixture of these choices.”

The path of least resistance is inflation, but governments like the United States, Canada and Britain, should they decide to “inflate away their debt”, brush up against central banks whose goal is to control inflation and unemployment levels through interest rates.

Trump as we have seen has repeatedly clashed with Fed Chairman Jerome Powell over interest rates (Trump wants them lowered, Powell has resisted, up to September’s cut). He also attempted to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook.

Inflation bomb

“Inflate away the debt” is a strategy where a government creates more money to pay its debts, causing inflation to rise. This reduces the real value of the debt over time, as it can be repaid with money that is worth less than when it was borrowed. (AI Overview)

Inflation in this way might be good for an indebted country but it’s bad for its citizens, who face higher prices for goods and services, and risks the creation of asset bubbles, say in real estate and stocks.

Like Hugo Dixon did for Reuters, The Economist in its omniscient way goes through the different scenarios at governments’ disposals for dealing with an excess of debt.

Rejecting the idea that “productivity growth, powered by artificial intelligence (AI), would relieve the state of difficult budget choices,” The Economist finally lays it out for all to see:

It is therefore increasingly likely that governments will instead resort to inflation and financial repression to reduce the real value of their high debts, as they did in the decades after the second world war.

Is this really a strategy to deal with public debt strangulation? It appears so. But The Economist wouldn’t be so bold as to support this notion, so it goes on to criticize inflation, which “harms the economy and society,” and “redistributes wealth unfairly.” Hell, it could even wreck the middle class.

The obvious example where this happened is Argentina, which, “plagued by inflation, went from being one of the world’s richest young countries to a middle-income economy that lurched from one crisis to the next.”

The fact that this is precisely what could happen to developed countries if they follow the “inflate their debt” approach, necessitates a warning by The Economist:

A decade ago, this newspaper urged emerging markets like Brazil and India to heed the parable of Argentina. Today our warning is for the world’s richest economies.

But wait. While US inflation soared to a 40-year high in 2022, a series of rate hikes by the Federal Reserve brought it down to near the Fed’s 2% target. So much for inflating away the debt, right? Wrong.

Inflation is making a comeback.

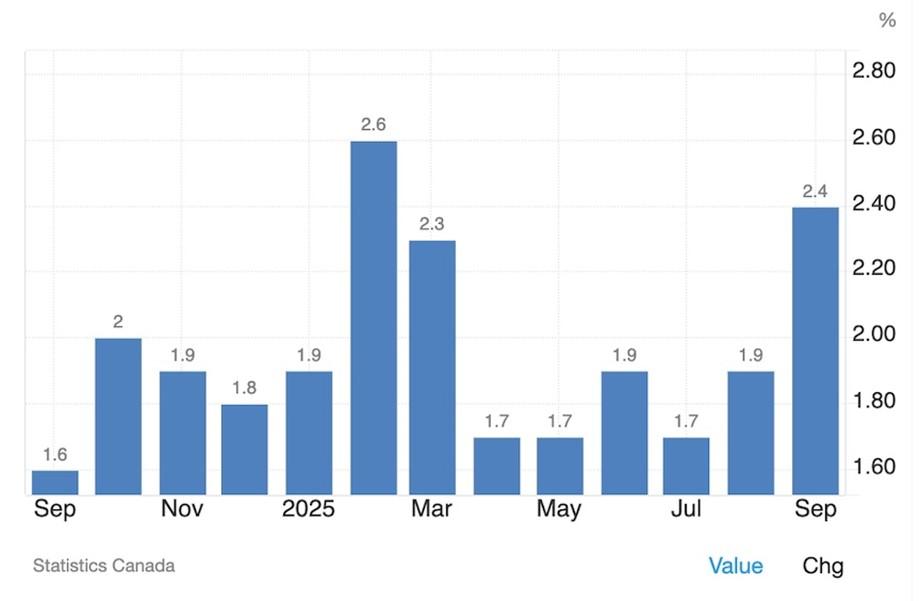

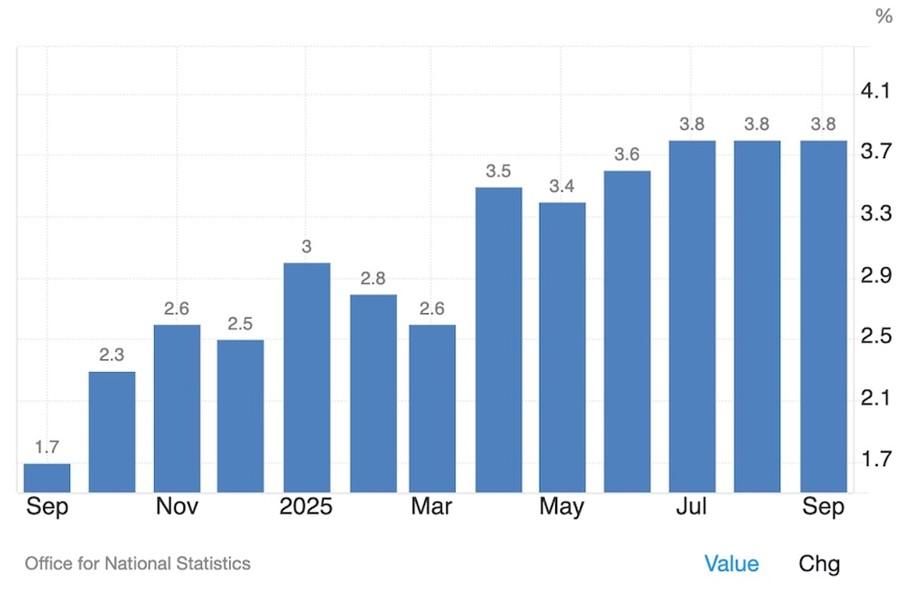

As the three charts below show, inflation over the past year has been on the rise in the US, Canada and Britain.

1-year US inflation (CPI). Source: Trading Economics

1-year Canada inflation. Source: Trading Economics

1-year UK inflation. Source: Trading Economics

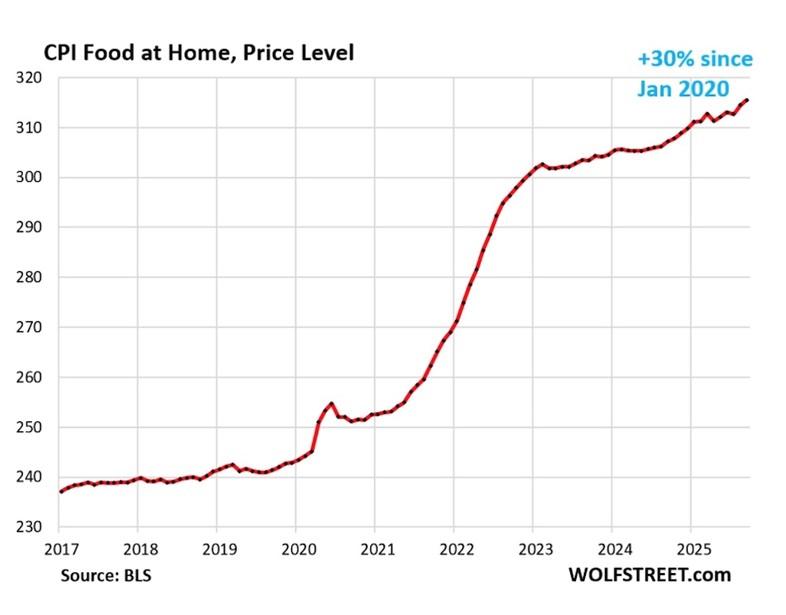

Wolf Street reports CPI for food at home has surged by 30% since January 2020, glibly noting, “Food prices are nothing to be trifled with.”

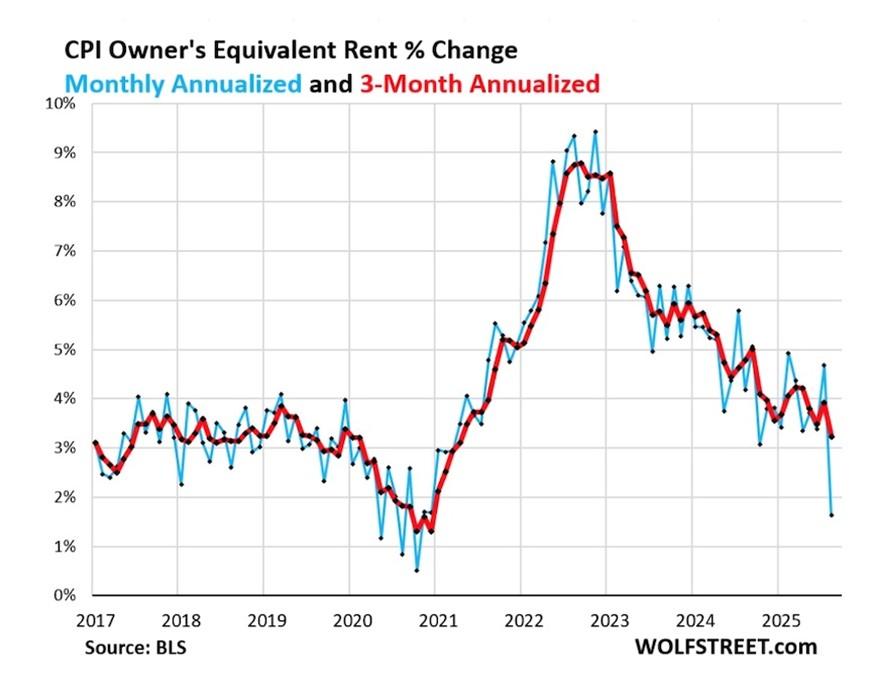

The publication on the same day headlined “something went awry at the BLS” (probably during the government shutdown — Rick) because a “massive outlier” in Owner’s Equivalent of Rent (OER) pushed down CPI, core CPI and core services CPI.

To clarify, OER is not a measure of rent, but instead, reflects the costs of home ownership. It is a significant portion of consumer price inflation, representing 26% of CPI, 33% of core CPI and 44% of core services CPI. As Wolf Richter states, “It moves the needle. CPI inflation would been a lot hotter without this outlier.”

So, what happened? OER rose by only 0.13% in September from August according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. This compares to 0.38% in August and compared to the 12-month range between +0.27% (May) and +0.41% (July). “Something went wrong there,” Richter observes.

Back to zero

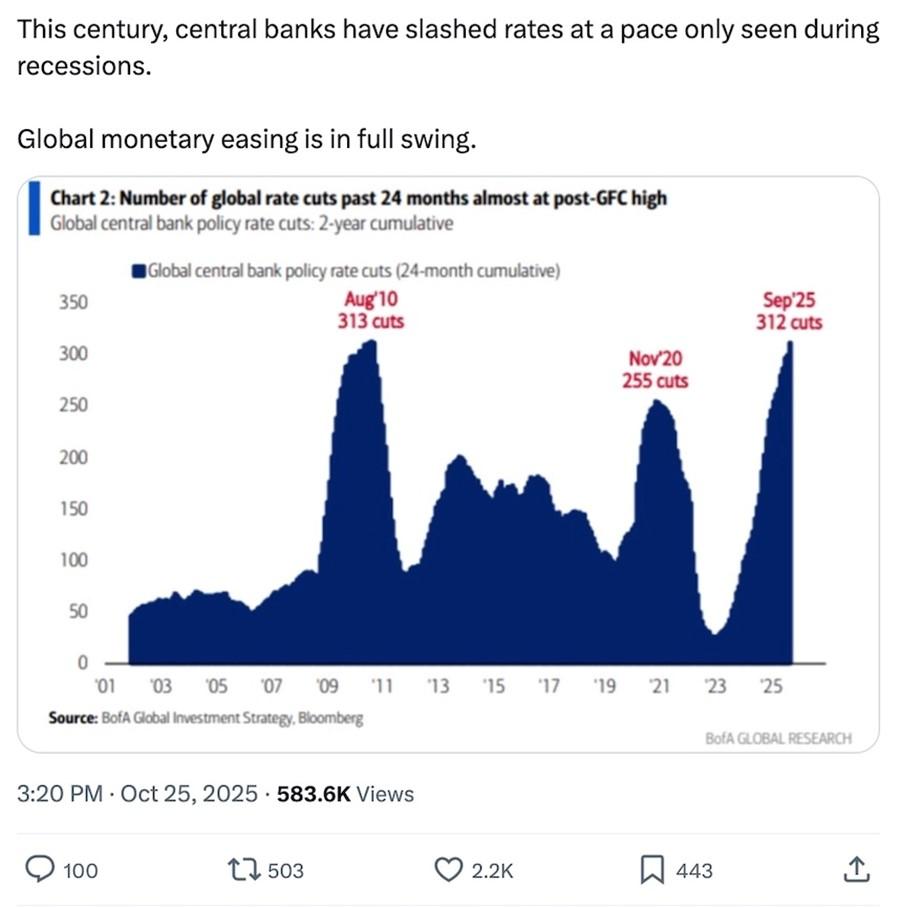

The rise in inflation coincides with a global monetary easing agenda. A post by The Kobeissi Letter on X says central banks have cut rates 312 times over the last 24 months, the second-highest total in at least 25 years. In fact, this is only one rate cut below the 2008 financial crisis response! The post continues:

By comparison, the global pivot before and during the 2020 pandemic brought 255 cuts. This also marks a massive jump from just 30 rate cuts during the 2022–2023 period. So far, 82% of world central banks have cut rates over the last 6 months, the highest share since 2020. This century, central banks have slashed rates at a pace only seen during recessions. Global monetary easing is in full swing.

Source: X

The Federal Reserve slashed interest rates by a quarter-point in September and it is expected to make two more reductions before the end of the year, according to the October CNBC Fed Survey. The Federal Open Market Committee is meeting this week to decide.

Rome, asset inflation and unaffordability

Asset Inflation… (From Rome to America: The Fall of Empires Through Debt and Currency Collapse) is required reading for anyone seeking to understand the current debt spiral the United States and most of the developed world finds itself in.

The first point by author John Walter is that America and its current debt trajectory mirrors the Roman empire’s fall from grace.

A bit of background. Rome in its heyday was an economic powerhouse sustained by conquest, trade across a vast empire from Britain to Egypt, and a stable currency, the denarius. Initially the coin was made of nearly pure silver, but by the 2nd century AD, the cost of maintaining its sprawling empire began to strain resources.

What happened next should be very familiar:

As military campaigns and administrative costs grew, Roman emperors resorted to debasing the denarius. By reducing its silver content, emperors like Nero and Trajan minted more coins to cover deficits, effectively inflating the money supply. By the 3rd century, the denarius contained less than 5% silver, down from 95% a century earlier. This devaluation eroded trust in the currency, driving up prices and destabilizing markets, a phenomenon akin to modern inflation driven by excessive money printing.

Rome’s reliance on borrowed funds to finance wars and public works mirrored modern deficit spending.

Eventually Rome was gripped by hyperinflation. By the late 3rd century, prices for basic goods such as wheat soared 1,000%.

The collapse of the denarius’s value eroded purchasing power, impoverished the middle class, and concentrated wealth among elites, deepening social divides.

Again, sound familiar?

Today, the United States, often described as a modern empire, faces a $37 trillion national debt, equivalent to 120% of GDP. Like Rome, the U.S. has relied on borrowing to fund military dominance, social programs, and tax cuts. Interest payments on the debt, projected to hit $1 trillion annually by 2030, mirror Rome’s unsustainable fiscal commitments. This debt, fueled by deficit spending, threatens to crowd out investments in infrastructure, healthcare, and education, much as Rome’s finances strained its public works.

The U.S. dollar, untethered from the gold standard since 1971, has lost 90% of its purchasing power since 1960, echoing Rome’s denarius debasement. The Federal Reserve’s policies, such as quantitative easing, have expanded the money supply, inflating asset prices while eroding real wages. A dollar in 1960 is worth roughly 10 cents today, forcing Americans to grapple with rising costs for housing, healthcare, and education, much like Romans faced soaring prices for basic goods.

Asset Inflation and Inequality Rome’s currency collapse concentrated wealth among landowning elites, while the U.S.’s asset inflation has enriched the top 1%, who hold 32% of national wealth. Stock markets and real estate, buoyed by low interest rates and stimulus, have soared, with median home prices reaching $412,000 in 2024, nearly five times median household income. This mirrors Rome’s growing divide between patricians and plebeians, as ordinary Americans struggle with unaffordable housing and stagnant wages.

Markets underpricing risky debt

While many have drawn attention to artificial intelligence as causing a bubble in AI stocks, that if it pops, could be worse than the dot-com crash, a potentially more dangerous situation is tight credit spreads.

This is the difference in yield between high- and low-risk bonds. Corporate debt and emerging-market bonds are considered risky compared to developed-country bonds.

As Bloomberg explains it, spreads on risky corporate debt are currently low by historical standards, meaning that markets are underpricing risk.

It isn’t that risky debt is any less risky. It’s that bond yields on long-term government debt, like 10- and 30-year Treasuries, are higher. Why? Because given the uncertainty in the US, bond investors need a higher rate to invest in longer-term bonds because these bonds are now considered less safe than previously, i.e., before Donald Trump.

The yield on the 10-year is currently 4.0% and on the 30-year it’s 4.6%.

Source: Trading Economics

Source: Trading Economics

As Bloomberg explains, Not only is the US government taking on a lot of debt, but the future of trade, inflation and the dollar looks uncertain. All of that increases bond yields.

It adds that the rise of private credit, discussed below, means that more capital is chasing risky bonds, which decreases spreads.

What’s the problem with underpriced risk? Bloomberg sees it as more dangerous than a stock market bubble popping:

When equities crash, people lose money. In a debt crisis, payments aren’t made, collateral becomes worthless, and firms go bankrupt.

Banking system at risk

Earlier this month, two car parts suppliers with multibillion-dollar debts in the private credit market — Tricolor and First Brands Group — went bust amid allegations of fraud, and two regional US banks uncovered a clutch of bad loans.

The collapse of Zions Bancorporation and Western Alliance Bancorp drew comparisons to the regional bank stress that followed the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in 2023.

Jamie Dimon, the boss of JP Morgan, said more “cockroaches” might scuttle out of the $3 trillion black box that is the private credit market, The Telegraph reported.

Private credit is a form of debt financing offered by non-bank lenders to borrowers, such as companies needing capital for expansion or real estate development. Instead of public markets, these loans are privately negotiated between the lender and borrower, often with customized terms to fit specific needs. This market has grown rapidly, particularly after the 2008 financial crisis, and is a significant part of the alternative investment landscape, with funds raised from institutional investors like pension funds and insurers. (AI Overview)

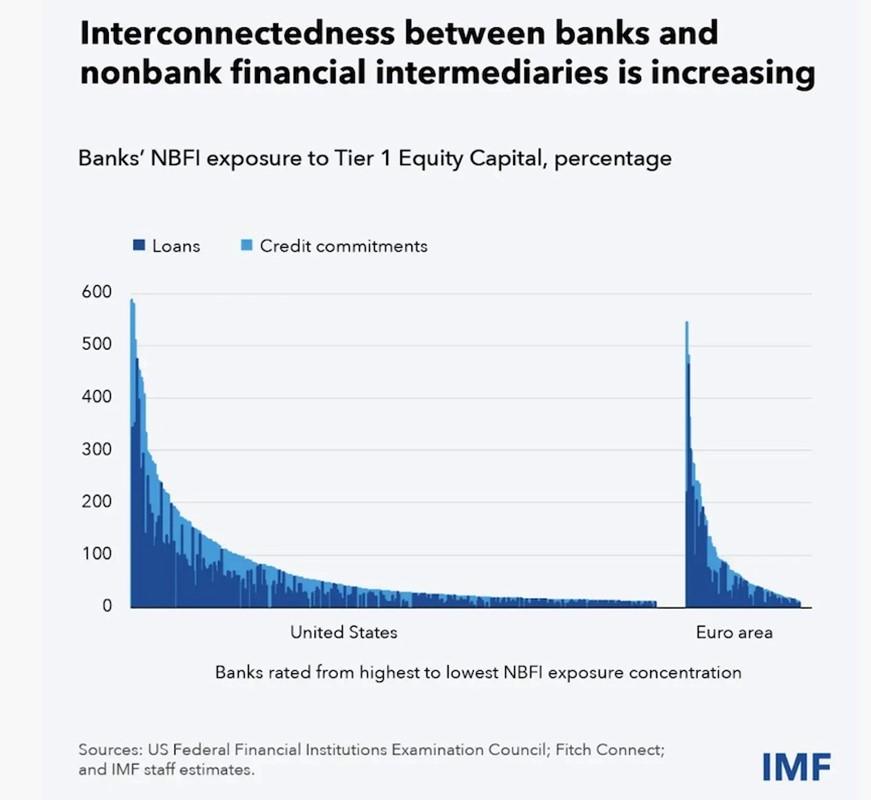

The Economic Times notes that Nonbanks now hold roughly half of global financial assets and account for half of daily foreign exchange market turnover, more than double their share 25 years ago.

The problem is that private credit’s interconnectedness with regular banks could amplify shocks if things go south.

The IMF warns that banks now have about $4.5 trillion of exposure to the “shadow banking sector,” a sum exceeding the size of the British economy.

Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director, told The Telegraph that the potential for a crisis to emerge from the world of non-bank financial institutions “keeps me awake every so often at night”.

Georgieva’s worry is that the lack of regulatory restraint has allowed the non-bank lenders not only to take bets that could be too risky, but also without ever letting in any outside light shine onto their activities.

If these institutions go bankrupt, it could cause contagion. The Telegraph explains what could happen:

Private credit funds are often illiquid, which means it is hard for investors to buy or sell their holdings. If fears develop about the funds’ viability, investors will try to sell, or redeem, their holdings.

The illiquidity might leave them able to sell only at a large loss. To prevent this, the private credit fund manager might try to block or delay redemptions.

This creates an incentive for investors to get out at the first sign of danger. And that reflex rush to the exit can create a more general sense of panic…

In the stampede, investors – including the banks – may need to sell other more liquid assets, like stocks and bonds, to cover their losses. These other assets will also likely be offloaded at fire-sale prices, and suddenly losses begin to spread across the market.

How government debt could cause the next financial crisis

While we’re into potential financial Armageddon scenarios, we need to return to the crush of government debt, which according to a recent headline in The Financial Post, “could play a starring role in the next great financial crisis.”

Soaring long-term bond yields graphed above are raising questions about how long the US government can service its debt, and whether it could precipitate the next financial crisis.

Remember, the States is now running a deficit of nearly $1.8 trillion or 6% of GDP, despite efforts by DOGE to rein in spending.

The breakdown could begin in the $29 trillion US Treasury market. According to the Brookings Institution, via The Financial Post,

A sustained breakdown in the U.S. Treasury market could cause a global financial crisis that erodes asset values, destabilizes financial institutions and pushes economies into recession. Moreover, the assessment suggested, it wouldn’t necessarily take a true default to trigger a crisis, just fears that the deteriorating fiscal situation would make a strategic default plausible.

Such fears could manifest in a significant decrease in the value of Treasuries, which would trigger a broad financial crisis. It could happen in the so-called “repo” market, overnight transactions that allow banks to balance their daily accounts and use Treasuries as collateral.

There’s also the impact on other governments that hold a significant portion of their foreign reserves in US. Treasuries. “A reduction in their value will weaken the position of governments across the world,” the FP quoted Juan Carlos Hatchondo, an economics professor at Western University who specializes in sovereign debt issues.

The fact that the global bond markets are more tightly integrated than previously increases the risk of contagion. We saw an example of this in 2024, when rising yields in Japan prompted a short burst of volatility across markets as so-called “carry trades” that feed demand for U.S. Treasuries were unwound.

While the timing of such an event is impossible to predict, because there is no “red-line number” that triggers a debt crisis, the US is increasingly more exposed to one.

A substantial portion of US debt will need to be refinanced at higher rates. As of June, greater than 31% of US debt — more than $10 trillion — was set to mature within a year.

“If one adds a budget deficit in excess of six per cent of the GDP, the Treasury must issue debt worth approximately 37 per cent of the GDP,” Hatchondo said. “If the market starts demanding a higher yield to compensate for the risk of holding U.S. bonds, debt growth will accelerate and can easily trigger a crisis.”

The founder of Bridgewater Associates, Ray Dalio, warned in his book ‘How Countries Go Broke: The Big Cycle’, that the US government debt situation is nearing the point of no return:

In his view, the country is headed for a classic “death spiral” because it will need to keep issuing bonds to pay its debt. The deteriorating fiscal situation will, at some point, cause investors to demand ever higher yields, layering on more debt at higher cost.

Of course, for the US government which holds the world’s reserve currency, the dollar, this isn’t a problem because they can just print money, if needed, to pay bondholders when the bonds mature.

Remember though, printing money to pay bondholders, or buying bonds through quantitative easing programs, is highly inflationary.

What they really need to do, according to Mark Manger, director of the global economic policy lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School, “is to not lower taxes like crazy and not spend like crazy.”

Good luck with that. Politicians are addicted to spending. In the United States, where lawmakers go to Washington to represent their constituencies, and are expected to lobby Congress for money, reining in spending means a path to almost certain electoral defeat.

Conclusion

During the 2025 fiscal year, the US spent nearly one quarter of all tax revenue just on paying interest on the debt.

Rising debt payments for fiscal year 2025 continue an accelerating trend in interest costs. With FY 2025’s interest bill now topping $1.22 trillion, it’s up by 7.3 percent compared to the previous fiscal year.

2024 was the last calendar year with interest spending under a trillion dollars. 2025’s interest payments will easily exceed $1 trillion, meaning the US now spends more on interest than on the military.

Source: Mises Institute

Source: Mises Institute

Source: Mises Institute

Source: Mises Institute

Citizen Watch Report helpfully distilled three recent Economist articles into three key points:

- The world’s richest governments are heading toward a slow-motion debt disaster.

- Sovereign debt rarely gets repaid honestly – it’s inflated away, or quietly defaulted.

- And no, economic growth can’t save us this time.

As we stated in the section on global debt, out of a clutch of bad options, the least bad, or the one of least resistance, is to inflate away the debt.

In the words of Citizen Watch Report, We’re not likely to see formal defaults. Instead, inflation and higher borrowing costs will do the work – an invisible tax on savers that “solves” the debt problem by eroding purchasing power.

Long-term lenders have noticed. Debt costs remain stubbornly high even after central banks started lowering interest rates. That’s not a mystery – it’s a vote of no confidence. Creditors no longer trust governments to manage their budgets, so they’re demanding higher payments to keep lending.

The next global crisis, The Economist warns, won’t come from banks or housing. It’ll come from governments themselves.

It’s interesting to note that since 1913, rich nations have almost never paid down debt through surpluses, spending cuts or real (after inflation) economic growth. Only one G7 country — our own Canada in the 1990s — managed to reduce debt through austerity.

Everyone else chose the politically painless path: inflation dressed up as policy success. More often, they’ve inflated it away.

Is it any wonder that central banks are choosing to own gold?

Subscribe to AOTH’s free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

MORE or "UNCATEGORIZED"

Eldorado Announces Strong Exploration Results of Multiple New High-Grade Zones in Canada and Greece and Increases 2026 Exploration Investment, Reinforcing Confidence in Discovery Strategy

Eldorado Gold Corporation (TSX: ELD) (NYSE: EGO) is pleased to announce the discovery of four new hi... READ MORE

First Atlantic Nickel Increases RPM Zone Strike Length 50% to Over 1.2 km and Width to Over 800 m from Phase 2x Drilling at Pipestone XL Magnetic Nickel-Cobalt Alloy Project

First Atlantic Nickel Corp. (TSX-V: FAN) (OTCQB: FANCF) (FSE: P21) is pleased to announce pos... READ MORE

McEwen Drilling Returns Significant Intersection at Gold Bar Mine Complex in Nevada: 5.55 gpt Gold over 44.2 Meters; Transformation into a Long-Life Mine Continues

McEwen Inc. (NYSE: MUX) (TSX: MUX) announces new drill results from the Gold Bar Mine Complex in th... READ MORE

Aya Gold & Silver Provides 2026 Outlook and Strategic Priorities

Aya Gold & Silver Inc. (TSX: AYA) (OTCQX: AYASF) is pleased to provide its 2026 outlook and pres... READ MORE

Highlander Silver Announces US$40 Million Strategic Investment by Eric Sprott to Accelerate Growth

Highlander Silver Corp. (TSX: HSLV) is pleased to announce that Mr. Eric Sprott, an arm’s l... READ MORE