Rick Mills – AMOC current could collapse within 20 years

The possibility of a major Atlantic Ocean current collapsing within the next two decades has the government of Iceland deeming it a national security concern, with officials strategizing worst-case scenarios.

Reuters reports Climate Minister Johann Pall Johannsson saying that Iceland’s ministries will be on alert and coordinating a response:

The government is assessing what further research and policies are needed, with work underway on a disaster preparedness policy.

Risks being evaluated span a range of areas, from energy and food security to infrastructure and international transportation.

What is the AMOC?

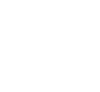

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is a large system of water currents that circulates water from south to north and back, in a long cycle within the Atlantic Ocean.

This system of deep-water circulation, sometimes referred to as the Great Ocean Conveyor Belt, sends warm water from the Gulf of Mexico to the North Atlantic, where it releases heat to the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. The cold water then sinks to great depths and travels all the way to Antarctica and eventually circulates back up via the Gulf Stream.

Without climatic disruptions, the currents move water around the globe, along with nutrients key to the survival of marine species.

But climate scientists have been raising concerns that rising temperatures are throwing a wrench into the conveyor belt-like currents system. Sensors stationed along the North Atlantic show that the volume of water moving northward has been sluggish, potentially affecting sea levels and weather. If the AMOC were to stop altogether, it could bring extreme climate change within decades, not centuries or millenia — a period so short it wouldn’t even register in geologic time.

Why would it stop?

New research reveals this key cog in the global ocean circulation system is currently at its weakest point in over 1,000 years, and is being further weakened due to the rise in global temperatures.

Studies by the Potsdam Institute and others have concluded that the AMOC is about 40% slower than during the mid-20th century, based in part on Atlantic Ocean temperatures and the size of grains on the ocean floor, which can reflect changes in deep-sea currents.

According to a 2024 study published in ‘Science Advances’, global warming is undermining heat exchange between ocean currents. To understand what this means, we need to introduce some earth science. Ocean currents are created due to differences in water density, or the weight of the water.

“The colder and saltier the water is, the greater its density, and the easier it is for its mass to sink. Whereas if the water is warm and fresh, it is lighter and therefore stays at the surface more,” Sandro Carniel, a climatologist and oceanographer at the National Research Center, explains via Renewable Matter.

This 10,000-year-old process has allowed northern Europe’s climate to be more temperate than it normally would be. Once the warm water masses moving from the Equator to the Arctic Circle reach their destination, they cool, become dense and sink, making way for more warm currents from the Equator.

The problem is that warming seas and melting sea ice are hindering the sinking of these great water masses.

“The huge amounts of melting ice are pouring an incredible amount of fresh water into the North Atlantic,” Carniel says. “Less and less salty and warmer waters are helping to lag the general circulation of currents.”

How do we know the Atlantic circulation is weakening?

In 2021, an international research collaboration known as RAPID collected readings from hundreds of sensors at more than a dozen buoys placed in the Atlantic Ocean roughly along 26.5 degrees North latitude.

The goal was to better understand how global warming is changing the AMOC, and how much more it could shift in the coming decades — even whether it could collapse. (MIT Technology Review)

Data from the RAPID moorings showed a general weakening in the Atlantic circulation from 2004 to 2012, with a sudden 30% drop from 2009 to 2010. That was likely a major contributor to an especially cold winter in northwest Europe in 2012, as well as rapid sea-level rise in that period along the northeastern US coast, reaching about 13 centimeters around New York. The slowdown was an order of magnitude larger than global climate models predicted.

The currents rebounded substantially in the years that followed. But the strength of the circulation is still below where it was when the measurements started. In fact, it has decreased even more than climate-change models predicted.

For years, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has downplayed a shutdown of the Atlantic circulation, calling it “very unlikely” this century. But studies dating back to 2017 note the climate models overstate the stability of the current because they don’t incorporate meltwater from the Greenland ice sheets.

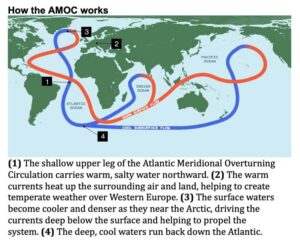

This variable had scientists talking about a so-called “tipping point”,

beyond which it is impossible for the AMOC to return to its previous state. According to a study published in 2021, the Atlantic circulation could be susceptible to too much change occurring too fast, causing the system to break down, if the water flowing from the ice sheets increases rapidly enough.

The signs include decreasing sea-surface temperatures and salinity in the North Atlantic, a salinity “pile-up” in the Southern Atlantic, and a characteristic shift in current patterns known as a “critical slowing down…

Niklas Boers, a professor of Earth system modeling at the Technical University of Munich and a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, found evidence of these warnings across eight different records, suggesting “an almost complete loss of stability.”

“In the course of the last century, the AMOC may have evolved from relatively stable conditions to a point close to a critical transition,” Boers wrote.

What would be the effects?

If the AMOC were to stop, temperatures in Europe would fall dramatically, wet seasons in the Amazon would flip to dry seasons, and coastal cities would experience sea rise in the tens of centimeters.

While the atmosphere is warming a few tenths of a degree every decade, a slowdown in the circulation of Atlantic currents would cause temperature changes of a few degrees every 10 years.

Researchers predict that some European cities could see a 5 to 15-degree Celsius drop in a few decades. Bergen, Norway, for instance, could become 3.5C colder every decade.

The Atlantic Ocean would rise by 70 cm (27.5 inches), drowning many coastal cities. Rainfall in the Amazon would be substantially reduced, and the Southern Hemisphere would get progressively warmer.

The predictions were obtained through computational models that simulated the effects of climate change over 2,000 years.

AMOC collapse — a coming climate catastrophe — Richard Mills

But let’s be clear. The slowdown or stoppage of the Atlantic circulation wouldn’t be anything like that imagined in the 2004 disaster movie ‘The Day After Tomorrow’. The popular Hollywood film shows the abrupt halt of the current flash-freezes the Northern Hemisphere over a few days, entombing New York in ice.

While the actual consequences are unpredictable, researchers at the Met Office Hadley Centre in the UK used a high-resolution climate model to determine what could happen. From MIT Technology Review:

Much of Europe could turn into a starkly different world… Within 50 to 80 years after a massive infusion of fresh water that halts the Atlantic circulation, sea surface temperatures drop as much as 15°C from the Barents to the Labrador Seas, and 2 to 10°C across much of the rest of the North Atlantic.

Sea ice drifts farther and farther south, reaching the northern tip of the United Kingdom in late winter.

The continent experiences extensive cooling as well. Winter storms intensify, become more frequent, or both. On average, most of Europe gets drier, aside from the Mediterranean during summer. But more of the precipitation that does fall arrives in the form of snow.

Given these cooler and drier conditions, surface runoff, river flows, and plant growth all decrease.

The Garonne River in southern France carries 30% less water during peak winter periods. Growth in the needleleaf forests of Northern Europe slows by as much as 50%. Crop production “decreases dramatically” in Spain, France, Germany, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Poland, and Ukraine…

Some models find that parts of Asia and North America could grow cooler as well. The slowing currents could disrupt the delivery of crucial nutrients, devastating certain fish populations and otherwise altering marine ecosystems.

As the Gulf Stream subsides and flattens, ocean levels could quickly rise eight to 12 inches along the southeastern US. The tropical rain belt could drift south, weakening rainfall patterns across parts of Africa and Asia [raising the odds of droughts and famines] and ratcheting up monsoons in the Southern Hemisphere…

The Reuters article about the AMOC and Iceland agrees that the collapse of AMOC could trigger a modern-day ice age, noting the last Ice Age that ended about 12,000 years ago. Winter temperatures across Northern Europe could plummet, bringing far more snow and ice.

How might an AMOC collapse affect Canada?

An AI Overview finds it would likely lead to cooler temperatures and sea-level rise along the Atlantic Coast, as well as increasing storm activity. The Maritime provinces would probably be most affected.

The phenomenon could also, as mentioned, destabilize rainfall patterns relied upon by subsistence farmers across Africa, India and South America, and could also contribute to faster warming in Antarctica.

The most shocking part of the Reuters story, though, is this paragraph:

Scientists have warned that the world is underestimating the threat that an AMOC collapse could become inevitable within the next couple of decades as global temperatures keep climbing.

For most of us reading this, that is easily within our lifetimes.

Has this happened before?

The short answer is yes.

The prevailing theory of what caused an abrupt freezing involves a large influx of fresh water from a large lake, called Lake Agassiz (now the Great Lakes), into the Atlantic Ocean likely via the St. Lawrence Seaway, which stopped the AMOC in its tracks, plunging Europe and much of the Northern Hemisphere into a relatively short ice age.

There is geological evidence of a sharp decline in temperature between the Pleistocene epoch and the current Holocene epoch.

The Younger Dryas is a term sometimes employed to explain the natural cycles of global warming and cooling. It refers to an interruption in the heating of the climate that occurred after the last global ice age that started receding about 20,000 years ago.

Within decades temperatures dropped 2 to 6 degrees C, causing the advance of glaciers and dry conditions. The Younger Dryas is named after the alpine flower whose leaves are found in lake sediments of Scandinavian lakes. Scientists discovered that vegetation during a previous warmer period was replaced by that normally found in a cold climate, such as the Dryas octopetala wildflower. The mini-ice age is thought to have lasted between 1,000 and 1,300 years, and like it started, also ended abruptly, within 40 to 50 years.

Renewable Matter says the last Atlantic Current halt occurred about 12,900 years ago, confirming the theory that it was due to the melting of Lake Agassiz, which caused large amounts of fresh water to spill into the sea. The AMOC halt, likely caused by a comet strike, was followed by 1,300 years of freezing.

New research

The collapse of the Atlantic circulation is no longer a low-likelihood event, states a recent (Aug. 28) article in The Guardian.

While previous models indicated that a collapse before 2100 was unlikely, the new analysis examined models that were run for longer, to 2300 and 2500. These show the tipping point that makes an AMOC shutdown inevitable is likely to be passed within a few decades, but that the collapse itself may not happen until 50 to 100 years later.

Bringing forward the doomsday scenario has to do with carbon emission models the researchers studied. They found that if carbon emissions continue to rise, 70% of the models lead to collapse, an intermediate level of emissions results in collapse in 37% of the models, and in low emissions, an AMOC shutdown happens in 25% of the models.

The study means that even if global temperature rise is kept to the Paris agreement standard of no more than 2 degrees C, or ideally, 1.5 degrees, there is a 25% chance of the AMOC collapsing.

“We found that the tipping point where the shutdown becomes inevitable is probably in the next 10 to 20 years or so. That is quite a shocking finding as well and why we have to act really fast in cutting down emissions,” said Prof Stefan Rahmstorf, at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, who was part of the study team.

“Even in some intermediate and low-emission scenarios, the AMOC slows drastically by 2100 and completely shuts off thereafter. That shows the shutdown risk is more serious than many people realise.”

In October 2024, 44 of the world’s leading ocean and climate scientists signed an open letter warning that the network of Atlantic ocean currents keeping the Earth’s climate stable could be on the brink of collapse, “sooner and with greater impact than has been previously estimated.”

The letter, quoted by Oceanographic magazine, and presented at the Arctic Circle conference in Iceland, cautioned that the stoppage of AMOC could lead to “devastating and irreversible climate impacts” for countries around the world. It noted countries in the Nordic region would bear the largest brunt.

The fallout could include significant changes in weather patterns, extreme temperature shifts, rising sea levels, and even disruption to marine ecosystems, the article states.

It presents an answer to those who believe that “global cooling” in the Northern Hemisphere will counter-balance global warming elsewhere.

“While a cooling Europe may seem less severe as the globe as a whole becomes much warmer and heat waves occur more frequently, this shutdown will contribute to an increased warming of the tropics, where rising temperatures have already given rise to challenging living conditions,” said the University of Copenhagen’s Professor Peter Ditlevsen, one of the 44 scientists who signed the letter.

But the main message is one of urgency, to shine a spotlight on a coming climate catastrophe that looms closer than anticipated.

The letter highlights the rapidity with which the AMOC is approaching a tipping point, beyond which it could enter an irreversible decline.

While the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) previously concluded that there is “medium confidence that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation will not collapse abruptly before 2100,” scientific research suggests this risk assessment has been “vastly underestimated” and that passing the tipping point is a serious possibility already within the next few decades, states Oceanographic.

Research from the University of Copenhagen published in 2024 found that, with 95% certainty, a collapse could occur between 2025 and 2095. The university’s study suggests that most likely the collapse will occur in 34 years’ time, in 2057.

Conclusion

If we believe the most recent studies, we have two, maybe three decades left before the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation stops moving, causing abrupt climate changes — up to 15 degrees colder or warmer — within a decade. This is based on the last time the AMOC collapsed, 12,000 years ago.

But the planet is much worse off than it was then. Along with rapid warming at the poles, and melting sea ice and glaciers, we have melting permafrost causing huge volumes of methane to escape into the atmosphere, collapsing polar vortices, and extended droughts happening all over Earth.

Suddenly the cliché, “I weep for future generations” sounds apt.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Subscribe to AOTH’s free newsletter

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

MORE or "UNCATEGORIZED"

Cerro de Pasco Resources Enters Project Development Funding Agreement with U.S. International Development Finance Corporation for Quiulacocha

Cerro de Pasco Resources Inc. (TSX-V: CDPR) (OTCQB: GPPRF) (BVL: CDPR) announces that it has ... READ MORE

NorthWest Announces Updated Mineral Resource at Kwanika Reflecting Strategic Shift to Higher-Grade Copper-Gold Focus

NorthWest Copper Corp. (TSX-V: NWST) is pleased to announce an updated mineral resource estimate for... READ MORE

Monument Reports Second Quarter Fiscal 2026 Results

Monument Mining Limited (TSX-V: MMY) (FSE: D7Q1) today announced its financial results for the three... READ MORE

Taseko announces First Cathode Harvest at Florence Copper

Taseko Mines Limited (TSX: TKO) (NYSE American: TGB) (LSE: TKO) is pleased to announce its F... READ MORE

Highland Copper Closes Sale of 34% Interest in White Pine for US$30 Million

Highland Copper Company Inc. (TSX-V: HI) (OTCQB: HDRSF) is pleased to announce, further to its press... READ MORE